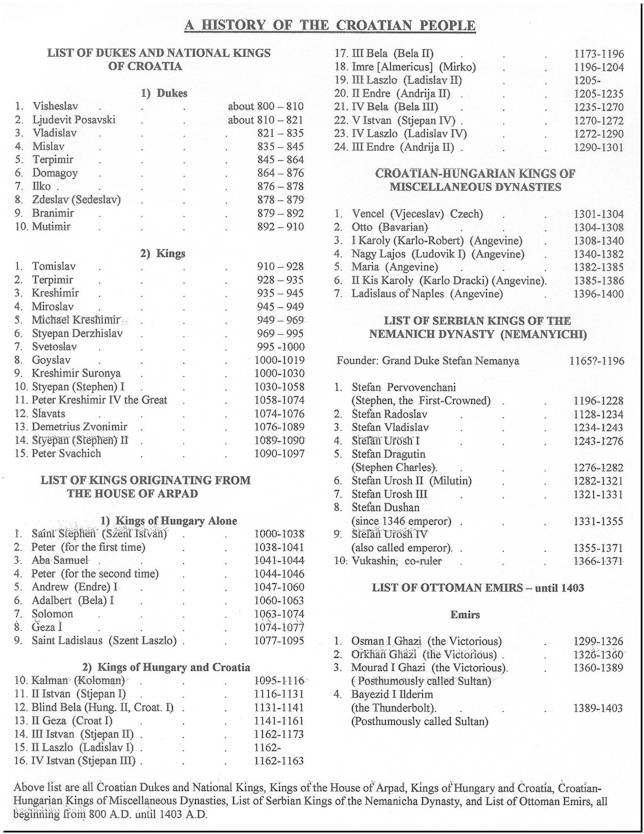

The Extinction of the Arpad Dynasty

Last Members of the Arpad Dynasty

Stephen V was a man of violent temper, ambitious and ruthless. After his victories over his father, he invaded Bulgaria. The death of Bela in 1270 made him the sole and undisputed ruler over a once more united Hungary. Shortly thereafter, he quarrelled with the Bohemian King Otokar Premysl II over the conquest of Carinthia and Carniola by his powerful neighbour. The war continued with changing fortunes until May, 1271, when a battle of the decision was fought in the area contained between the town of Moshon and the creek of Rabtsa, west of Gyoer. In this engagement, the forces of Otokar were repulsed but not defeated. Thereupon the rulers came to terms: King Stephen renouncing all his claims to Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola, while Otokar promised that he would not support the pretender, Stephen Posthumous, son of King Andrew I. In the meantime, Stephen Posthumous died in Venice leaving behind his widow, the Venetian Tomassina Morossini, and a son, Andrew the Venetian.

During Stephen’s reign, the princes of Kerk became the masters of the city of Sen in 1271, while Joachim Pektar was the maritime banus. In the summer of 1272 Stephen decided to pay a visit to Naples by making a trip through Dalmatia. On his journey, he took along his elder son Ladislaus in order to show the lad the world. He soon discovered that the task of being a mentor was a trying one, and he left the boy in the abbey of Topusko, while he himself proceeded on his journey south. For this neglect of his paternal duty, he had to pay dearly, for on his arrival at Bihach on Una he was stunned by the message that his son had disappeared from the Topusko monastery. The boy had been kidnapped by banus Joachim Pektar, probably in complicity with Queen Elizabeth, a Kumanian by birth.

Upon hearing the news Stephen immediately returned. His anxiety and the fatigue of the search undermined the king’s health and forced him to return to Budavar. His followers continued to search for the prince and found him being held in the town of Koprivnitsa. They laid siege to the town, but in the meantime King Stephen died early in August, 1272.

Ladislaus III – 1272-1280

With the king’s death the siege of Koprivnitsa was lifted while the banus Joachim Pektar hastened with the prince to Szekes Fehervar where he was received by his mother Elizabeth. Here he was crowned as Ladislaus III (1272-1290). He was known by the name of his mother’s kin, therefore the “Kumanian.” Up to Stephen VI, the prestige of the king in Croatia was untarnished but, after his death there was an almost complete dissolution of the royal authority.

The oligarchs asserted their power. At first Ladislaus’ youth, then his weakness and extravagance reduced the royal power to a vanishing point. The over-confident oligarchs now began to quarrel and fight among themselves for the office of banus and possession of the large estates. New families of magnates came into prominence. The Giessingen barons, émigrés from Germany, were granted extensive estates in the county of Krizhevats. Then the Gut-Keledi clan, likewise a German family, also occupied large estates in the counties of Zagreb and Krizhevats around Koprivnitsa.

The native princes of Babonichi of Voditsa, later on of Blagay, were masters of the entire province from the Carniola frontier to the river of Verbas, with important towns along the Kupa River and the Sana. The princes of Kerk established themselves along the seacoast from Tersat down to Sen, extending east to the foothills of Gvozd (Kapela). Finally, the Bribirian princes from the clan of Shubich were masters of the district of Bribir and swayed over the Dalmatian cities, with the exception of the Venetian Zadar.

Conditions in Croatia

While King Ladislaus was a minor, his mother, Queen Elizabeth, took over the reign. Her chief advisor was the banus of Slavonia, Joachim Pektar, who later became treasurer of the kingdom. Joachim was replaced in the office of banus by Matthews of the Chak-Trenchin clan. His administration is remembered by the fact that on the 20th of April, 1273, he called for the first Slavonian parliament. According to the extant records, this “general congregation” deliberated on judiciary matters, administration of justice, military obligations and taxes.

In Croatia and Dalmatia, Prince Paul of Bribir, son of Prince Styepko became again the “maritime banus.” In Slavonia Mathias Chaky was replaced by Henry, the Giessingen. But Henry himself became a rebel and in an uprising against Ladislaus and his mother, he lost his life. Now the king’s younger brother Andrew was appointed Croatian duke. Yet, being a minor, the actual ruler was his mother Elizabeth. Not even this change could prevent the outbreak of a Croatian rebellion under the leadership of the Babonichi princes. The movement was aimed chiefly at the queen’s advisor, Joachim Pektar, and did not subside until this man lost his life (1272). With his death, soon every vestige of the Gut-Keledi clan was wiped out in Slavonia.

Popular Routes: Split to Korcula, Korcula to Split, Dubrovnik to Korcula, Korcula to Dubrovnik

Battle on the Moravian Field

In the meantime, important changes took place in neighboring Austria. In 1273 Rudolf the Hapsburg was elected German king, and he immediately summoned the Bohemian king Otokar to return the Babenberg heritage to Germany. Since the Bohemian king refused to comply with Rudolf’s request, war broke out which ended in the battle on the Moravian Field (August 26, 1278). In this engagement, Rudolf was aided by the Hungarians, and thus defeated his opponents while Otokar met a hero’s death on the battlefield.

As a result of this battle, the Hapsburgs became masters of the old Babenberg possessions, and immediate neighbors of the Bohemian, Hungarian and Croatian kingdoms. They were now in a position to meddle in the internal affairs of these three states and they did, with the aim of uniting them into one single realm under the Hapsburg standard. They actually achieved this ambition, but only after centuries of effort and under the stress of unusual developments.

Even after the death of Joachim Pektar peace was not restored in Croatia and Dalmatia. The situation became still more muddled after the death of Duke Andrew in the summer of 1278. King Ladislaus was, at that time, the only legally recognized member of the Arpad dynasty since the Court steadily refused to admit the dynastic legitimacy of Andrew the Venetian, son of Stephen. In the meantime, the Giessingens and Babonichi were joined in these quarrels by the princes of Kerk; while in Dalmatia the Venetians attacked the Kachich clan of the Omish area and wiped it out completely.

However, banus Paul of Bribir put up a short defense in his stronghold of Omish (1280). This was an ideal situation for Andrew the Venetian to enforce his claims to the Croatian duchy. Moreover, he was aided by the Giessingen clan which raised a rebellion in 1289 against King Ladislaus and invited Andrew to Croatia. Escorted by his uncle Albert Morossini, Andrew landed early in 1290 in the Venetian Zadar and set out north on a campaign of conquest. His venture was not propitious, for in the enclave of the Drava and Mura Rivers near the locality of Shtrigovo, he was made prisoner by some grandees who turned him over for safe-keeping to the Austrian duke Albert I, son of Rudolf of Hapsburg. But the wheel of fortune soon turned toward the young adventurer, for King Ladislaus was killed by his Kumanian kin. In the absence of a prince of the Arpad lineage, the Hungarian high nobility invited Andrew from Vienna to ascend the Throne of Hungary.

Andrew II – 1290-1301

Soon after he established himself on the Hungarian throne, Andrew was confronted with the opposition of three powerful contenders, denying the legitimacy of his Arpad lineage. One of them was Rudolf of Hapsburg. This ruler insisted that King Bela III turned Hungary and Croatia over to the German emperor Frederic II for protection during the Tartar invasion (1241), thus submitting to German sovereignty. Accordingly, in August, 1290, Rudolf assigned both kingdoms to his son, Duke Albert of Austria.

Pope Nicholas IV was the second contender. The pontiff put forth the claim that both kingdoms were the lien of the Holy See, and that he alone had the authority to dispose of them. Queen Maria of Naples, sister of King Ladislaus III, claimed her own right to the throne, passing on this claim to her son Charles Martel. In her contention, she was supported by the Pope and consequently, Charles Martel was crowned by the papal legate in Naples in 1292, as King of Croatia and Hungary.

In the meantime, Andrew was legally crowned in Szekes Fehervar and, having the support of the greatest part of Hungary, quickly asserted his power in the face of opposition. First, he settled accounts with Albert the Austrian, as his most dangerous opponent, by declaring war on him and defeating him. Thereupon Albert renounced, by the peace treaty of Hinesburg, all his rights to Hungary.

However, it was far more difficult to settle the matter with the Court of Naples. Charles Martel was supported by almost all of Croatia from the Drava to the Neretva, and even by John the Giessingen, Banus of Slavonia. In view of this, Andrew, with his armed forces, crossed the Drava River, asserting his authority throughout. Yet on his way home from a successful campaign, he was treacherously seized by John the Giessingen and thrown into prison. After paying a huge ransom, Andrew regained his freedom in 1292. The king was now joined by the Babonichi clan which brought to Hungary the king’s mother, Tomassina Morossini. She was promptly appointed duchess of Croatia.

Princes of Bribir

Both the Court of Naples and Andrew II prized highly the friendship of the princes of Bribir, and especially that of banus Paul. In order to attach Paul to his side, King Charles II of Naples granted him, in the name of his son, Charles Martel, all Croatia from Modrush in the north to Hum in the south. This ownership carried the right of inheritance, with the further provision that all Croatian noblemen who lived in that area became vassals of banus Paul and his successors. Outbidding the Neapolitan patent, King Andrew did the same in 1293, giving Paul and his clan all of the Croatian-Dalmatian banate and the title of banus as a hereditary honor. With these grants, the princes of Bribir became the first magnates of Croatia, and the banus office became hereditary in their family, passing from father to son without any royal interference, or even approval. At the same time, the Babonichi princes made an effort to establish themselves as hereditary bani of Slavonia, while in Bosnia the princes of the Kotromanichi clan succeeded in founding their own dynasty.

The Last Years of Andrew’s Reign

After a short period of peace, the war flared up in 1295, in the course of which Zagreb and the nearby countryside became the scene of bitter fighting. The suburban royal town of Gradetz stood by King Andrew, while the Kaptol stronghold of Zagreb supported Charles Martel. In that year (1295), however, Charles Martel died, bequeathing the Croatian-Hungarian crown to his son, Charles Robert. King Andrew himself had no son to succeed him on the throne, so in 1299 he proclaimed his uncle Albert Morossini as his successor. This attempt failed, for a general rebellion broke out in the country, and the Estates espoused the cause of Charles Robert.

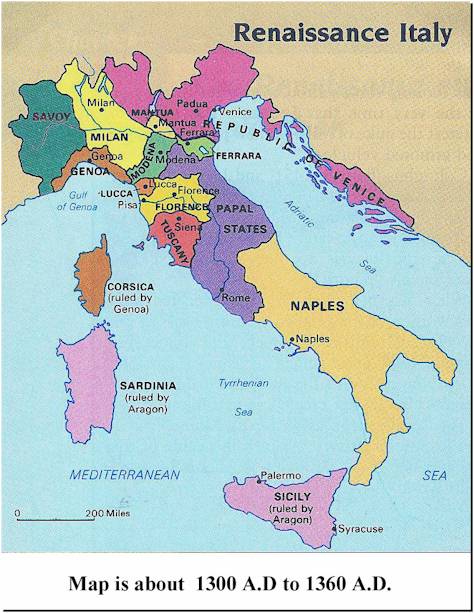

George, the Prince of Bribir, brother of banus Paul, went to Naples in August, 1300, and brought the young prince to Croatia. Shortly thereafter, on January 14, 1301, Andrew died. With this event, the male line of the House of Arpad became extinct. Upon the news of Andrew’s death, banus Paul brought Prince Charles Robert to Zagreb, where he was received by Prince Ugrin of the clan Chak-Ilok. Thence he was escorted to Ostrogon (Esztergom) and there in March, 1301, the young prince was crowned by Gregory, Archbishop of Ostrogon, as Charles I, King of Hungary and Croatia. Meanwhile, Just about this time, the Renaissance began in Italy (see map below).

The House of Angevins on the Croatian-Hungarian Throne – 1301-1409

Charles I – 1301-1342, Struggle with Rival Kings

Charles Robert was merely a boy, 12 years of age when Prince George of Bribir brought him from Naples. Almost all Croatia recognized him, but Hungary was divided into a number of factions. By marriage ties with the Arpad dynasty there were three claimants to the throne: The Neapolitan King Charles II, whose wife was the Hungarian Princess Maria, daughter of Stephen VI; the Bohemian King Ventseslav II, son of the late Otokar Premysl II and Kunigunde, grand-daughter of Bela III who passed on his claim rights to Ventseslav; and Otto of Bavaria, son of Bela’s daughter Elizabeth.

The majority of Hungarian magnates, headed by the palatin Mathias Chak of Trenchin decided in favour of the Bohemian Prince Ventseslav. They brought him to Szekes Fehervar and crowned him as Ladislaus V (1301-1304), King of Hungary. In consequence, a bloody civil war broke out between the supporters of the two kings. Pope Boniface VIII himself cast the weight of his office in the struggle with such determination that Ladislaus V left Hungary in 1304, giving up the fight.

Thereupon the Hungarian Estates proclaimed and crowned Otto of Bavaria as their king. He actually ruled from 1304 to 1308, although his faction was weak. Since his strongest support came from Transylvania he went there to pay a visit to Ladislaus Apor, whose daughter he intended to marry. But that high-handed magnate took him prisoner and seized the crown of St. Stephen, which Otto always carried with him. When he regained his freedom, Otto returned in 1308 to Bavaria, renouncing all claim to Hungary and Croatia.

The third rival of Charles came from Serbia. The Serbian ex-king Styepan Dragutin was connected with the House of Arpad by his wife, Catherine, daughter of King Stephen VI. He entered into an agreement with the Transylvanian Duke Ladislaus Apor, by the terms of which his son Ladislaus would marry the duke’s daughter, receive the crown of St. Stephen and become the crowned King of Hungary. This intrigue was checkmated by the successful campaign of Charles in Sirmium, in which Prince Paul of Gara won distinction and established the historical fortunes of his family. Thus the Apor episode was brought swiftly to its inglorious end.

Papal Interference

Meanwhile, the Holy See sent Cardinal Gentilis to Croatia and Hungary in order to prepare the way for peace. Early in November, 1308, Gentilis arrived at Budavar and by his wise and tactful bearing soon won over the chief opponents of Charles. He also had the Estates called, where he began to explain the right of the Holy See to the Hungarian-Croatian throne. But when, during his explanation, loud murmurs and shouts betrayed the hostile state of mind of the assembly, the Cardinal promptly changed his argument and conceded to the Estates the right of free election.

Thereupon Charles was elected by acclamation and generally recognized as legitimate ruler and sovereign. This move also ended forever the papal claim to the crown of Hungary and Croatia. However, the problems connected with Charles’ enthronement were not yet at an end, for the crown of St. Stephen was still in the hands of the Transylvanian Duke Ladislaus Apor. Hence, Cardinal Gentilis consecrated a new crown, having declared the old one null and void. So, Charles was crowned for the second time in Budavar on June 15, 1309, by Thomas, Archbishop of Ostrogon. At the coronation Archbishop Peter of Split represented Prince Bribir while Henry Giessingen, banus of Slavonia, and the brothers Stephen John and Radoslav Babonichi also sent representatives to witness the ceremony.

Yet in the eyes of the people a coronation with a substitute crown did not have the glow of legitimacy. By old tradition, three conditions were prerequisite to a valid crowning: first the crown of St. Stephen; second, Szekes Fehervar as the place of the coronation, and third, the presence of the Archbishop of Ostrogon to perform the ceremonies. Therefore, it became necessary to recover the hallowed crown of St. Stephen from the hands of the brigand. After much haggling and upon the delivery of ransom money, Duke Apor finally released the relic. Charles was then crowned for the third time in Szekes Fehervar with the venerated crown of St. Stephen. The ceremony was performed on the 27th of August, 1310, again by Archbishop Thomas of Ostrogon. Only then did Hungary recognize Charles I as king in due form.

But peace was not restored. The grandee Mathias Chak of Trenchin refused to recognize the young king, and challenged his power for another ten years. Only the death of Mathias in March, 1321, dispersed the forces he had gathered. Even then the disorders continued. Felician Zakh, a Hungarian magnate, attempted to strike the king down with his sword in April, 1330, but failed in the attempt. With the death of this seigneur, peace was finally restored in Hungary, and Charles finally became a full-fledged ruler in his kingdom.

Banus Paul and Zadar

While in Hungary the Oligarchs were gradually trampled down by the king’s rising power, developments in Croatia took a different course altogether. Here Charles I was never able to fully consolidate his power. The Croatian magnates and nobility recognized him as their king, but they were carrying on in their own dominion quite independently. Foremost among these were the princes of Bribir, especially their senior, the Croatian banus (banus Chroatorum) Paul, and since 1299 also “Sovereign of Bosnia.” The authority of banus Paul extended at the beginning of the 14th century from the mountain ranges of Govzd to the Neretva River and from the sea to the Bosna River. Only Venetian Zadar was not in his possession. But he decided to extend his sovereignty over that important port also.

Developments in Italy favored his plans. So when Pope Clement V (1305-1314) excommunicated the Venetians because of their seizure of Ferrara, and released all the Venetian subjects from their oath of loyalty, the banus succeeded in persuading the rebellious Zadar to stage an armed insurrection against Venice (1311). However, in the middle of the war, which lasted for three years, Banus Paul died (May, 1312). According to some, he was assassinated by the Bosnian heretics. He bequeathed to his son Mladen the title of banus, together with his extensive dominion.

Banus Paul ranks among the greatest men of Croatian history, wise, deliberate and resolute. He nearly restored the might of the national Croatian rulers, uniting the largest portions of the Croatian State. For two centuries Paul and his son Mladen were considered by historians as independent rulers. Mladen (1312-1322) was, in fact, a highly educated and courageous man, but hot-tempered and impetuous. Although the situation favored his course, he failed to complete the war with the Venetians to his advantage and Zadar was again forced to surrender to Venice (September, 1313). This time, however, the terms of submission were less Draconian than those in the past.

Downfall of Banus Mladen

Mladen’s failure in the Zadar affair tempted Venice to bring about his downfall altogether. Soon the Republic found suitable men in Shibenik and Trogir, and early in 1322 they raised a rebellion against Mladen and surrendered both cities to Venice “for protection.” In a further move the Venetians promoted a strife among the factions of Croatian nobility, with Duke Nelipich of the Svachich clan as the leader of the malcontents. The group was joined by Paul, brother of Mladen, who was promised the office of banus. From this intrigue a civil war broke out in Croatia, and King Charles decided to take advantage of the situation. Consequently, he sent aid to the opponents of Mladen through the banus of Slavonia, Ivan Babonich, while he himself made a trip to Croatia. Late in the fall of 1322, Banus Mladen was defeated by his enemies in the battle of Liska, near Trogir.

In the meantime, Charles himself arrived at Knin and summoned the Estates to a parley which was attended by Mladen under royal safe conduct. There he was treacherously seized by the king and taken to Hungary. Details of this event are not clear. While the extant sources disagree about his captivity, Mladen never returned from Hungary, and it is assumed that he was put to death by the ungrateful king who owed his very throne to Mladen’s family.

The title of Croatian-Dalmatian banus was now conferred upon John Babonich, banus of Slavonia. The Bosnian banate was also removed from the authority of the Bribir princes. Styepan Kotromanich was appointed banus of Bosnia and made a vassal of the king.

Duke Nelipich

When he appointed Ivan Babonich as the sole banus of the Croatian lands, King Charles directed him to restore the royal power in that country as it had been in the past. The banus not only failed to achieve this task, but aroused the Croatian magnates to such an extent that they joined in a defensive alliance against the king, entered into an agreement with Venice, and captured the royal city Knin. The leader of the resistance was the same Duke Nelipich who had fought Prince Mladen, and whose political power and ambitions he now inherited. Disappointed by his failures, the king dismissed Ivan Babonich, but his successors, Nicholas Omodeyev (1323-1325) and Mikats Mihalyevich, were even less successful. Not even the royal decree of 1325 proved effective. By this decree Charles strove to restore the ancient glamour of the name banus and to raise his authority above that of the grandees. The magnates took this patent as a challenge to their own power, and Duke Nelipich answered it in 1326 by striking a fatal blow at the army of Banus Mikats in a decisive battle, thus frustrating the king’s attempt to subdue the Croatian barons.

As a result of this defeat, all southern Croatia, from the districts of Lika and Kerbava down to the Tsetina River, became free and out of the reach of royal power. Only the princes of Kerk remained loyal to the king, as did, of course, Slavonia, with her Banus Mikats. They remained loyal because previous grants were confirmed by Charles and further expanded in 1323 by the gift of Gat and Drezhnik counties and a number of sizeable towns.

Another consequence of the victory of Duke Nelipich was the seizure by Venice of the coastal area from the Zermanya River to the mouth of the Tsetina. The Venetians managed to persuade the citizens of Split and Nin (Spalato and Nona) to surrender to Venice “for protection.”

Skradin and Omish (Scardona and Almissa) were the only free cities in this Venice-controlled territory remaining in the possession of the Bribir princes. Taking advantage of the general confusion, the Bosnian banus Stephen Kotromanich detached from Croatia the entire area between the Tsetina and Neretva Rivers, including the districts of Imotski, Dumno, Livno and Glamoch, setting up from these Croatian counties a province named “the Western Lands” or “Tramontane.” Over the rest of Croatia Duke Nelipich ruled as a sovereign, establishing his residence in the stronghold of Knin. He spent most of his time feuding with his enemies, especially the princes of Bribir and raiding the Dalmatian cities. He died in 1344.

The Last Years of Charles’ Reign

Charles I reigned peacefully in Hungary and Slavonia and lived amid pomp and glamour never witnessed before in the courts of Temeshvar and Vishegrad. Even in Zagreb he built a royal residence. In Slavonia the Banus Mikats Mihalyevich (1325-1343) ruled with an iron hand. For example, he crushed the resistance of the powerful Babonich clan and seized their town of Stinichnyak (1327) for the benefit of the king.

In spite of his domestic problems King Charles did not neglect the field of foreign policy, for he aspired to the crowns of Naples and Poland. In fact, when his uncle Robert, King of Naples, remained without a son, the younger son of Charles, Andrew, was betrothed to Robert’s granddaughter Johanna. Then the young man was sent to Naples for education as the future occupant of the throne. At the same time, Charles’ elder son Ludovic was trained to occupy the throne of Poland besides that of Hungary and Croatia. Charles’ wife Elizabeth was the sister of the Polish King Kazimir, another childless monarch, who obtained in 1339 the promise of the Polish Estates to elect Ludovic as his successor.

In the south Charles scored another important success with the capture of Belgrade in 1319, which, up to its seizure by the Turks, remained a bastion of Hungarian power in the Balkans. At his death (July 16, 1342) Charles I left behind three sons: Ludovic, Andrew and Stephen.

Ludovic I, the Great – 1342-1382, End of the Croatian Oligarchy

While still a 17-year-old boy, Ludovic inherited a vast dominion, with all its power and problems. Full of enthusiasm, determination and reliance on his good fortune, he plied to his immediate tasks. And indeed, after many wars and campaigns this ruler gave his state a compactness and significance which it never possessed before. For this reason the Hungarian historians call him Ludovic the Great (Nagy Lajos).

The young king immediately set to untangling the complicated Croatian situation. This task was simplified a great deal by the passing of the powerful Duke Nelipich (1344). The duke’s widow, Vladislava of the Gussich clan, took over the vast dominion as the guardian and caretaker for her young son John Nelipich. At the king’s behest Banus Nicholas of the Hahold clan invaded Croatia in the same year (1344), advanced to the walls of Knin and began to storm it. But the heroic Vladislava, fighting “like a lioness” repulsed the attacks. However, seeing that she would not be able to hold out indefinitely, she entered into negotiations with the banus, following which he left Croatia.

Aroused over this rebuff, King Ludovic set out at the head of an army 30,000 strong. Upon arriving at Bihach on the banks of the Una River, the king pitched camp with his host. As the news of this movement reached Vladislava, she came with her son Ivan to the king’s camp, took the oath of loyalty and surrendered her stronghold of Knin. Ludovic acquitted her of the “lifetime of treason” of her husband, and confirmed her son Ivan Nelipich in all his ancestral possessions, including the city of Sen and the Tsetina district. Thus, the power of the Nelipich clan was broken and from then on its members became loyal subjects of the king.

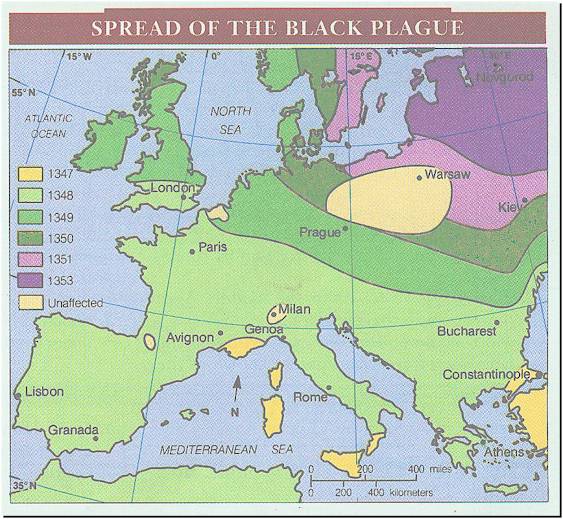

The Loss of Zadar and War with Naples

Upon the news of the king’s arrival at Bihach, the city of Zadar declared its loyalty. This move of the rebel city led to a new war with Venice, in which Zadar sustained a long siege. Yielding to the frantic appeals of its citizens for help, King Ludovic came to Zadar in the summer of 1346 with an army 100,000 strong. But the campaign failed, because, through the treachery Banus Stephen Kotromanich, and his own poor generalship, he lost the battle. Embittered over his defeat, Ludovic left Zadar to its fate, and returned to Hungary. Moreover, he made a truce with Venice for eight years (1348). In the meantime, the citizenry of Zadar, exhausted by starvation and disease (Black Plague), surrendered under oppressive terms after two years of heroic defence. (See the map below which uses color to indicate how the Black Death spread from one country to another over time. The plague, which was of unknown origin at that time, killed over 100 million people in Europe.)

During his stay before Zadar Ludovic managed to compose his differences with the princes of Bribir. Prince George, son of Paul, and brother of Banus Mladen surrendered to Ludovic the well-fortified and important town of Ostrovitsa and received in exchange the town of Zrin in Slavonia. Thus Prince George became the founder of the famous Zrinski family. Through the loss of their key stronghold, the power of the Bribir princes fell to a low ebb. Moreover, the branch that remained in Croatia soon died out, gradually losing its former presence and significance. With the collapse of the Nelipich and Bribir clans, the oligarchy of the Croatian magnates came to an end. In consequence, Ludovic restored the royal power in Croatia, which had practically ceased to exist there since the reign of Ladislaus III, the Kumanian.

The chief reason why Ludovic sacrificed the cause of Zadar and made an eight-year truce with Venice was the assassination of his brother Andrew at Aversi, near Naples. Realizing that he would never get the satisfaction he desired through negotiations, he set out at the head of his army to Naples, conquered the entire kingdom, and put to death all those guilty of the assassination of his brother. Only Queen Johanna, considered the chief offender, escaped his wrath (1348). But when Ludovic returned to Hungary, new disorders broke out, calling for another campaign overseas. Rather than squander his forces on Naples, which he could not hold forever, he gave up further plans of conquest and finally ceded the kingdom of Naples to Queen Johanna in 1352.

Marriage Tie with the Bosnian Dynasty

During the first years of Ludovic’s reign and his preoccupation with Croatia, Venice and Naples, the Serbian King Styepan Dushan acquired a large territory at the expense of Byzantium and raised his state to such a height of power that in 1346 he proclaimed himself “emperor (Tsar) of all Serbians, Bulgarians, Albanians and Greeks”. Then he directed his ambition toward the conquest of the Hum district (Herzegovina), which together with Bosnia, was the province of the banus Styepan Kotromanich, a vassal of King Ludovic I. Dushan broke into Bosnia but the resistance was stubborn and he withdrew in 1350.

Adding to the prestige which now accrued to Stephen Kotromanich came the betrothal and marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to King Louis I 1353. Stephen, however, did not long survive this climax of his career and left the Bosnian throne to his gifted nephew Tvartko, who was at that time a youth of 15 (1353-1391). Then, late in December, 1355, the great Serbian Tsar Styepan Dushan fell victim to the Black Plague. After his death, the Serbian power brought the kings of Hungary temporary relief, although this respite was attended by the prospect of a disaster that was to befall the Christian nations of the Balkans and central Europe.

The Second War with Venice

As the eight-year truce expired, Venice gained possession of the stronghold of Skradin and was bent on seizing the cities of Klis and Omis. This forced Ludovic into a final showdown with the Republic. He started a campaign for the liberation of all of Dalmatia, including the islands and towns. In order to assure victory, he planned to conduct the operations not only in Dalmatia and Croatia, but to invade also Serenissime’s Italian possessions, in order to separate the island-city from the mainland. In execution of his plan, the king began to organize a great army in Zagreb, pretending that he was about to wage war against Serbia. Suddenly he turned west and declared war on the Republic (1356).

Caught unprepared, Venice offered to return all the Dalmatian cities except Zadar. But the king rejected the terms and the war went on for two years. In Croatia and Dalmatia, the army was led by the Banus Ivan Chuze of Ludberg. Split and Trogir promptly surrendered, while the other cities soon followed suit. Resistance was offered only at Zadar, where fierce battles were fought. At the same time, Ludovic’s armies campaigned successfully in the north of Italy, and the Republic finally gave in. The peace treaty of Zadar (February 18, 1358) ended the war. By the terms of this covenant, Venice renounced all her Dalmatian cities and islands from the Bay of Quarnero to the city of Drach (Durazzo). Thus, Kotor and other coastal cities became free, while the Doge gave up his title of “Duke of Dalmatia and Croatia,” which the heads of the Republic had borne since 1,000 A.D. Through this settlement the Dalmatian cities and islands were returned to their legal king and the Croatian kingdom, while the Venetian authority was suppressed along the Croatian coastland for a long time to come.

Dynastic Troubles in the Anjou Family – 1382-1409

Shortly after the death of Ludovic I the Hungarian magnates crowned his elder daughter Maria (1382-1385) as if she had been Ludovic’s son (“Coronata fuit in Regem”). Since Maria was only 12 years of age, her mother Elizabeth Kotromanich acted as a regent. She was a simple and ambitious woman, fond of intrigue. Her chief advisor was the Hungarian palatin Nicholas of Gara (Gorjanski), an intelligent but selfish man. The first task of the queen mother was to see how she could acquire the Polish throne, as well as the Hungarian-Croatian throne for Maria. But the Polish Estates rejected her decisively since they no longer wanted their sovereign to reside in the Hungarian capital. However, they were willing to place the younger daughter Hedwig on the Polish throne, and after lengthy negotiations, they crowned her Queen of Poland. Thus they separated Poland from Hungary. The next year Hedwig was married to the Lithuanian prince Wlodzislaw Yagiello, founder of the Polish dynasty of Yagielloni (1386).

Strife in Croatia

Throughout this period important and serious changes were taking place in Croatia, where the centralistic policies of both Anjou kings and the enthronement of a woman caused widespread disaffection. This strife came as a boon for the expansionist policy of the Bosnian king Styepan Tvartko, for he aspired to the whole territory south of the Drava River. As soon as he heard of the change on the Hungarian throne he sent emissaries to some of the Dalmatian cities and certain Croatian magnates. The first to accept his invitation was the Prior of Vrana, Ivan Palizhna, but the Dalmatian cities and most Croatian barons turned deaf ears.

When the plans of Tvartko became known in Budavar, palatin Nicholas Goryanski offered a defensive alliance to Venice which was declined. At this juncture the queen mother Elizabeth decided to go herself to Croatia and effect a compromise with the malcontents. Upon the news of the queen’s mother coming to Croatia, Ivan of Palizhna raised a rebellion in Vrana. However, the aid which he had expected from Bosnia failed to materialize. Vrana had to surrender and Ivan Palizhna escaped to Bosnia, while Maria and Elizabeth installed themselves and a glamorous retinue without further opposition at Zadar. By the end of November, 1383, the Croatian barons appeared reconciled to the crown and a brief lull followed. After this, palatin Nicholas effected a compromise with the king of Bosnia, ceding to him the city of Kotor in 1385.

The capricious and unpredictable rule of Elizabeth and Maria created disaffection not only among the magnates of Slavonia but in Hungary as well. The malcontents were headed by the Horvat family of Vuka county. Outstanding leaders of this clan were Paul, bishop of Machva, and Ladislaus. They were joined by many Hungarian barons, including two officials of the royal court: Judge Nicholas Szechy, formerly a Croatian banus, and the treasurer Nicholas Zambo.

Confronted with the league of the malcontent Slavonian and Hungarian magnates, the Court first attempted a conciliation through palatin Nicholas of Gara. A compromise was arrived at by the treaty of Pozsega and was signed in May, 1385. But this arrangement was not of long duration, and when the nobility became convinced of the lack of sincerity on the part of Elizabeth and the palatin, it decided to find another sovereign in the person of the King of Naples, Charles of Durazzo (Drach), the only surviving male member of the Anjou dynasty. He was also the only foreign prince acquainted with the laws and constitution of Hungary and Croatia.

Exactly at that time, Maria’s fiancé, Sigismund of Luxemburg, broke into Hungary with a large army and proceeded to marry the 15 year-old Maria. Having achieved his purpose, he again returned to Bohemia. In the meantime Bishop Paul Horvat went to Naples and invited Charles of Durazzo to take over the throne of Hungary and Croatia. Charles was willing and went to Hungary, where the parliament in Budavar elected him king. The young queen Maria renounced her throne and Charles was crowned in the year 1385 in Szekes Fehervar as King of Hungary and Croatia.

Charles II and Maria

Charles of Durazzo assumed the name of Charles II, but his reign was limited to a few days because in February, 1386, Queen Elizabeth and the palatin Nicholas Gara had him assassinated, in the royal palace itself, by Balazh Forgach, a Hungarian magnate. Once again the youthful Maria was on the throne (1386-1395).

Elated over the success of their intrigue, Elizabeth and Maria made an excursion to Slavonia in order to pay a visit to Nicholas Gara, who was reinstated in the office of palatin. The assassin, Count Balazh Forgach, was a member of the party, together with a number of trusted grandees. They all headed for the town of Gara, residence of the palatin, but they never arrived there. Early in the morning of July 25, 1386, as they left the neighboring town of Djakovo, the royal party was ambushed by the forces of the Horvat brothers and their friends. A fierce fight ensued, in the course of which palatin Nicholas of Gara, Balazh Forgach and other courtiers were killed, while Elizabeth and Maria were taken prisoner.

The women were then sent to the seacoast, and kept in Novigrad, near the town of Nin. There Ivan of Palizhna, their custodian and the banus of Croatia, had Elizabeth strangled before the eyes of her daughter Maria. The life of the young queen was spared. This took place toward the middle of January, 1387. It was done, many believe, upon the insistence of the Court of Naples, in revenge for the murder of Charles of Durazzo.

King and Emperor Sigismund – 1387-1437

Informed of the tragedy of Djakovo and Novigrad, Sigismund hastened to Hungary where a party of the peers elected him their king and immediately crowned him in Szekes Fehervar. Sigismund made it his first task to deliver his wife Maria from the Novigrad prison. For this purpose he entered into an agreement with the Republic of Venice and the latter sent him a fleet of vessels with which to invade Novigrad from the sea. On the land side the stronghold was besieged by the troops of Prince Ivan of Kerk (Frankapan) and an army sent by Sigismund. After a long siege, banus Ivan of Palizhna released the queen early in June, 1387 under the condition that his own troops be allowed to withdraw unharmed from the stronghold.

At the same time the king’s army, headed by Nicholas (Gara) Goryanski, son of the assassinated palatin, fought so successfully in southern Hungary and Slavonia that the Horvat brothers, Styepan Tvartko and the Serbian Prince Lazarus, had to retire their forces into Bosnia. In this struggle, the youngest Horvat brother, Ladislaus, was killed.

Both the surviving brothers became active in Bosnia under King Tvartko, who relied on their wisdom and generalship until his death in 1381. His successor Styepan Dabisha sought conciliation with Sigismund and in 1393 signed a peace treaty in Djakovo, by the terms of which Sigismund was to inherit the Bosnia throne in case of Dabisha’s death. They further agreed to the fate of the Horvat brothers, who were thus finally seized by Sigismund. As his prisoners they were sent to Hungary, where the king took a cruel vengeance upon Ivanish, tying him to the tails of two horses and having his body torn apart. The fate of Bishop Paul is unknown, but he was probably incarcerated in some cloister where he is believed to have died in 1394. With the death of these two national heroes, the rebellion in Croatia was crushed.

Disaster at Nicopolis – 1396

The expansion of Turkish power in the Balkans came about simultaneously with the sedition in Croatia, the developments in Bosnia, and the Serbian disaster at Kosovo (1389). Sigismund himself was alarmed at the Turkish conquests and sought and obtained help from Germany, England, Poland and France. With an army of 40,000 men he turned against Sultan Bayazid, who at that time was making preparations for the siege of Constantinople. The purpose of Sigismund’s campaign was to destroy the Turkish power in Europe. Crossing the Danube near Orshova he came to Nicopolis on the Danube and laid it under siege. On September 25, 1396, however, Sultan Bayazid appeared with a superior army and completely destroyed the Christian forces. Sigismund saved his own life by boarding a barge and sailing down the river to the Black Sea. There he rested for a short period and at the beginning of the next year (1397), he returned through Constantinople and Dubrovnik to Hungary. The Ottoman victory at Nicopolis consolidated the Turkish power on the Balkan peninsula for many centuries to come.

Excerpts from “A HISTORY OF THE CROATIAN PEOPLE” by Francis R. Preveden, copyright 1955, pgs 111-121, 132

Compiled by: Marko Marelich, Retired Mechanical Engineer, San Francisco, California, U.S.A. May 2008