Martin Luther and Reformation – Catholic and Other Religions in Europe 1500-1600s

Martin Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, Germany. Luther’s father, a hard-working miner, wanted his son to be a lawyer. So in 1501, Luther began studying law at the University of Erfurt and graduated with a BA in 1505.

One day in 1505, Luther was caught in a thunderstorm and was thrown to the ground when a bolt of lightning struck nearby. Like most men and women of this time, Luther believed that God could come to the aid of humans. In the storm, he cried out, “Help, St. Anne, and I will become a monk.” True to his word, that same year Luther ceased studying law and joined the monastery in Erfurt. Luther was a model monk, and in 1507 he has ordained a priest. A year later, Luther was selected from among his peers to teach at the University of Wittenberg. As a monk Luther had struggled to understand the true nature of godliness. The church thought that the performance of religious ritual and good deeds was necessary to ensure the soul’s salvation. Luther worked hard to satisfy the church and save his soul. But he worried that his actions might not satisfy God.

Luther’s fears vanished, however, when he read St. Paul’s letter to the Romans: “He who through faith is righteous shall live.” (Romans 1:17). To Luther, Paul’s message seemed clear: the path to God is through faith alone, forgiveness was not something the church could grant, not was it something individuals could achieve on their own. Instead, it was given by God to each person who accepted him. This theory became known as “justification by faith”, meaning that a person could be made just or good, by his or her faith in God.

Luther’s belief in justification by faith led him to question the Catholic Church’s practices of self-indulgence. He objected not only to the church’s greed but to the very idea of indulgences. He did not believe the Catholic Church had the power to pardon people sins. Rather, Luther thought that salvation could be achieved only through God’s mercy. No one needed to seek or buy salvation through the church.

By nailing his theses to the church door, Luther was not acting like a heretic. He was simply inviting other scholars to respond to his ideas in a debate, an ordinary method of learning at universities of his days. At first, no one accepted Luther’s invitation. Over the next few years, however, his Ninety-Five Theses sparked a religious movement to reform the Catholic Church. Because the reformers were protesting against what they felt to be the abuses of the Catholic Church, they came to be known as Protestants. And because they wanted to reform the Catholic Church, that is, improve it by making changes, their movement is known as the Reformers.

Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were soon translated from Latin into German. Within a year, his ideas were known throughout Europe. As one historian put it, they spread “…as if angels from heaven themselves had been their messengers.” Encouraged by his success, Luther wrote hundreds of essays between 1517 and 1546, in which he stresses justification by faith and criticised church abuses. Finally, in 1520 Pope Leo X issued a bull – a statement of the Pope’s authority – condemning Luther and banning his works. Defying the Pope, Luther publicly burned the bull. The break with the church was then complete. In January 1521 Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther.

Meanwhile, through all this process, Luther explained all his Ninety-Five Theses and the reason for his objections. He showed the practices as proof of how greedy and corrupt the Catholic Church had become. Luther challenged the church to define itself – if it could. He read over one of his thesis: “Why does not the Pope, whose riches are at this day more ample than those of the wealthiest of the wealthy, build one basilica of St. Peter’s with his own money, rather than with that of poor believers?” Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were really an invitation to scholars to debate certain church issues. He had no idea that his challenge to the church would light a fire of protest and change that would sweep across Europe, and cause the reaction of Pope Leo X to excommunicate him from the Catholic Church.

However, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, decided to give Luther one final chance. In 1521 at a meeting of Worms, Germany, the Emperor demanded that Luther recant, or take back, his teaching. Facing church officials and an excited assembly of people, Luther refused. He said in part, “I do not accept the authority of Popes and councils. My conscience is captive to the word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything. Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise.

Popular Routes: Split to Korcula, Korcula to Split, Dubrovnik to Korcula, Korcula to Dubrovnik

God help me. Amen.” A near-riot broke loose. Luther strode out, his hands raised in triumph. Yet the Emperor later declared him an outlaw whom anyone could kill without punishment. Fortunately for Luther, he had a powerful friend in Frederick the Wise, Prince of Saxony. The Prince arranged a pretend to kidnap of Luther and hid him away for about a year in the castle at Wartburg. Here, Luther translated the Bible from Greek into German. His translation allowed the Germans people to read the word of God without having to rely on the interpretation by the priest. Luther continued to write work in which he attacked the church or discussed books of the Bible. His teaching eventually inspired a new Protestant religion called Lutheranism. This new religion would continue to oppose the once all-powerful Catholic Church.

Why did Luther’s ideas, which challenged the centuries-old Catholic Church, succeed? First, many people recognized the widespread corruption within the church and were eager for reform. Second, Luther wrote and spoke with conviction. His words were immensely appealing to the people. The printing press, developed in Europe about 1450, also contributed to Luther’s success. Printed pamphlets containing unbound essays on current topics could spread new ideas quickly to many people. By 1523 about a million copies of Luther’s pamphlets were in circulation. As the Reformation spread, it gained the support of European peasants. In 1524 and 1525, arguing that everyone was equal under God, a group of poor German peasants took up arms against their wealthy landowners. Known as the Peasant War, this revolt was badly organized and lacked strong leadership. Government armies quickly crushed the uprising. The peasants were surprised and disappointed to discover that Martin Luther did not support them in the Peasant War. In the pamphlet called Against The Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants Luther criticized the rebels for seeking economic gain in the name of God. As a result, Luther lost the support of many social reformers.

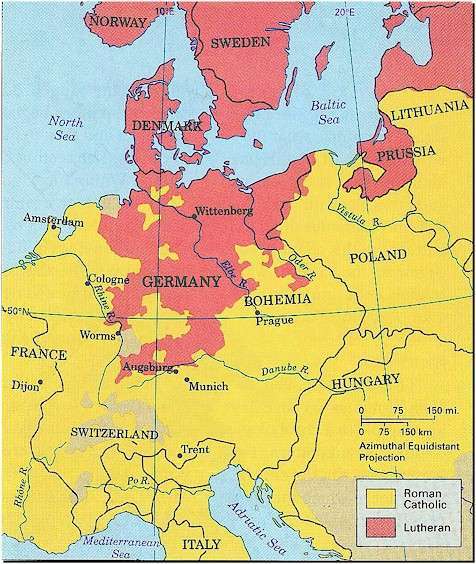

However, Luther’s ideas became popular with the German princes. Luther did not believe that the church should own property. He also thought that rulers should appoint clergy members. Thus, Luther favoured a more powerful role for rulers and weaker church authority. Many German princes who wanted freedom from the Pope’s authority favoured Protestantism. Others remained Catholic because they depended on the support of the Pope. Eventually, the differences between those German princes erupted in war. From 1546 to 1555, war raged between the Catholic and Protestant princes. Finally, in 1555, a compromise called the Peace of Augsburg, was reached. This compromise permitted each German prince to decide which religion would be allowed in his state. Most rulers of northern Germany chose Protestantism, and most in southern Germany remained Catholic. Many people had to move to states that allowed them to practice their own religion.

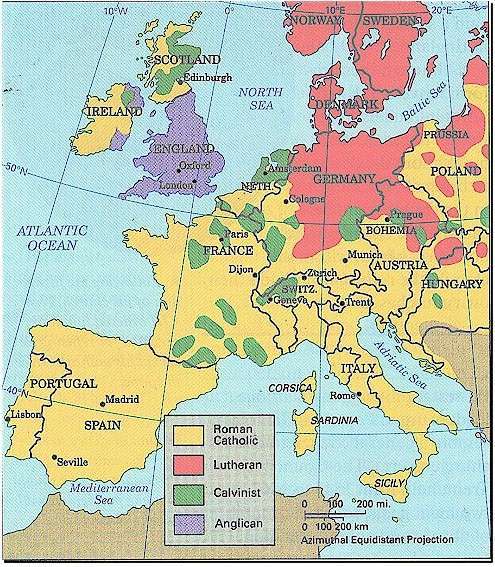

By 1560, the Reformation was established in Germany and, as you can see on the map above, in much of the rest of Europe.

In the early 1500s reform spread throughout Europe. Three of Martin Luther’s ideas became the centre of the debate. One idea was justification by faith. The second was the idea that the Bible was the only authority for Christians, rather than the law of the Catholic Church or Papal bulls.

The third was a belief in a priesthood of all Christians denying the special powers that priests had in the Catholic Church. Around 1517 when Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses, Ulrich Zwingli, a Swiss priest working in Zurich, brought the Reformation to that city. He urged Christians to study the Bible on their own and deepen their faith.

After Zwingli’s death, John Calvin, a Frenchman educated in law, continued to teach the ideas of the Reformation. Forced to flee France in 1534 where the Catholic Church had been harassing Protestants. Calvin moved to Switzerland. The city of Genoa soon became the centre for a movement called Calvinism.

Calvinism differed from other movements of the Reformation in one important way. Calvin taught that God had already chosen, or predestined, a special group of believers for salvation. This theory is known as predestination. Luther also accepted predestination but thought that people could never know whom God had chosen.

Calvinism emphasized being devoted to God and leading a disciplined life. According to Calvinists, a person who could maintain such conduct was probably a member of God’s chosen group. Calvinist church services were plain. No images of saints hung on the walls; no organ accompanied the singing.

Nothing appealing to the senses interfered with what the worshiper experienced as his or her spiritual link to God. Calvinists also followed a strict code of moral behaviour. Laughing or making noise in the church was prohibited.

So were fortune-telling, gambling, and even dancing at social gatherings. Councils elected by church members enforced this code of behaviour, as well as other laws of the Calvinist church. By the time Calvin died in 1564, Calvinism had taken root in Scotland, England, France, Italy, Bohemia, Poland, and the Dutch Netherlands.

One Protestant group called the Anabaptists, lived by an even stricter moral code than that of the Calvinists. The Anabaptist movement began in Zurich around 1525 among a group of dissatisfied followers of Zwingli. They believed that the state was made up of sinners.

Therefore, the Anabaptists believed, true Christians should withdraw from the state and form a separate community. Both Catholics and Protestants openly opposed the Anabaptists. They resented the Anabaptists claim that members of all other religious groups were sinners. Anabaptists were widely harassed, and many were executed. Those who survived fled to Poland and Holland.

Not all religious reform movements had religious causes. In 1533, King Henry VIII of England was excommunicated for divorcing his wife and marrying another woman. So Henry set up a new church – the Church of England.

In 1534 the English government recognised the monarch as the supreme head of the new church. Although independent of the Pope, the English church remained basically very similar to the Catholic Church in its principles and practices.

Not until Henry’s son Edward VI became king in 1547 did a Protestant religion gain a strong following in England. Although this reform movement had different beliefs, they shared the same basic motivations: the desire to bring about changes in the church. And because those changes were not coming from within the church, the reformers created their own church.

During the 1400’s many priests recognised that reform needed to be made. They realised that selling indulgences was corrupt, and they protested against such abuses. Reforms came slowly.

However, as more and more people left the Catholic Church to join the Protestant movement, Catholic leaders urged Pope Paul III to assemble a general council to discuss church reform. The Council of Trent, held from 1545 to 1563, set two main goals: to rid the church of abuses and uphold traditional Catholic beliefs. This movement within the church became known as the Counter-Reformation.

To rid the church of abuses, the church also encouraged the founding of new orders or special religious groups. Many of these were modelled after the Society of Jesus, founded by the Spanish priest named Ignatius Loyola in 1540.

Jesuits, as the members of the order were called, took vows of poverty and obedience. The Jesuits were noted for their educational and missionary works. They worked tirelessly, spreading Catholicism in other sections of the world, to the people of America, Africa, and Asia.

In addition to encouraging the spread of Catholicism, church officials tried to halt the spread of Protestantism. Their methods were often extremely harsh. For example, the official in Rome revived the Inquisition –a church court to judge and convict heretics. However, this court often abused its power.

Many Protestants who appeared before it was tortured. Others were sentenced to death when they refused to change their beliefs. The church officials also established the Index of Prohibited Books.

This list of banned books included books by Calvin and Luther. The Counter-Reformation helped to correct many church cases of abuse. However, it could not stop the spread of Protestantism. Never again would a single religion dominate Europe.

Compiled by Marko Marelich, Retired Mechanical Engineer, San Francisco, California USA, October 2005