The Statute of the town and island of Korčula from 1214

… It was perhaps as early as 1214 in order to protect the Island’s community that they drew up their first legislation collected in the communal Statute. When the knez (rector) of Dubrovnik, Marsilius Georgij, a proponent of Venetian interests, imposed himself on the inhabitants of Korčula and became their knez, he approved the existing statutory regulations and in 1265 with the islanders’ agreement, passed a new Statute whose text has been preserved until the present day. This Statute of Korčula is the oldest legal code of the Croats, and after the Russian 11th, or 12th-century code (Pravda) it is the oldest existing Slav legal record. Therein lay its world historical-legal and cultural value.

I.

The Adriatic island of Korčula (on which the town of Korčula is also situated) had, like the rest of Croatia, a stormy history.

The Croats’ Slavonic ancestors came from the north-east and settled in the regions they now inhabit in the 7th century.

At the time these territories were under the rule of Byzantium which, after the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, was considered its sole legitimate heir. In fact, already in the middle of the 2nd century B.C. the Romans had begun to make incursions along the eastern Adriatic coast, fighting against Illyrian tribes living in this region. During these incursions, the Romans were assisted by the Greek colonists who also lived there, especially on the islands, and in particular on Vis. Centuries went by before the Slavs arrived and, in the meantime, all the inhabitants of this region were Romanized and later with the spreading of Christianity also Christianized.

The conflict between the Slavs and the Romans was particularly strongly felt along the Adriatic coast where the latter were concentrated. However, the hostilities between these communities, which differed considerably by their ethnic origin, their religion and language, could not go forever. The survival instinct led them to establish economic as well as other contacts. The final result of such a symbiosis was that the Romans became Slavonicized and the Slavs Christianized. Thus the Croats accepted Christianity and outnumbered the Romans.

The Slavs gradually established their own ancient national states, such as ancient Croatia. However, during the medieval period they suffered different fates, and owing to invasions of foreign powers their peoples were partly or entirely subjugated and often changes hands. Thus, at a very early stage, the Croatian population on the island of Korčula and in other parts of Dalmatia became aware of the territorial pretensions of the young Venetian Republic. It was perhaps as early as 1214 in order to protect the island community that they drew up their first legislation collected in the communal Statute. When the knez (rector) of Dubrovnik (getting to Dubrovnik), Marsilius Georgij, a proponent of Venetian interests, imposed himself on the inhabitants of Korčula and became their knez, he approved the existing statutory regulations and in 1265 with the islanders’ agreement, passed a new Statute whose text has been preserved until the present day. This Statute of Korčula is the oldest legal code of the Croats, and after the Russian 11th, or 12th-century code (Pravda) it is the oldest existing Slav legal record. Therein lay its world historical-legal and cultural value.

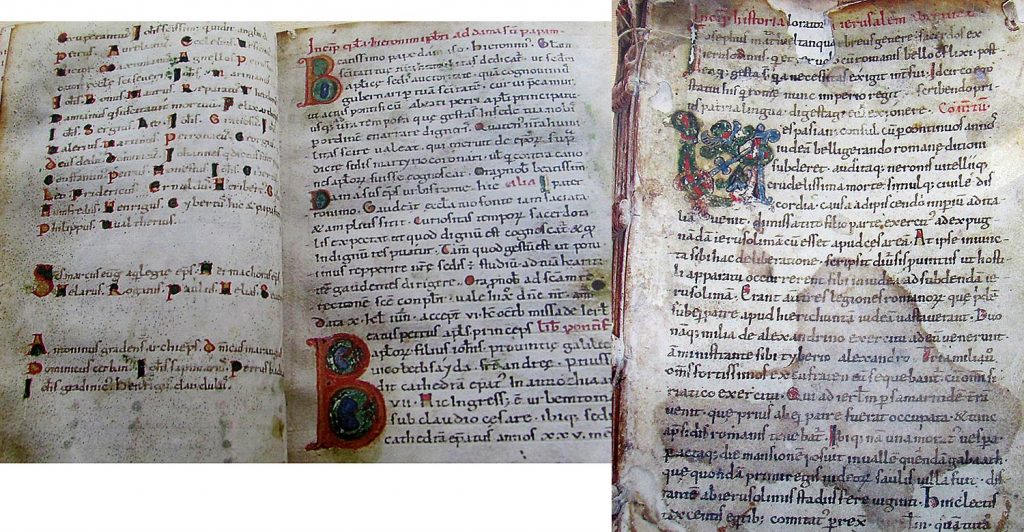

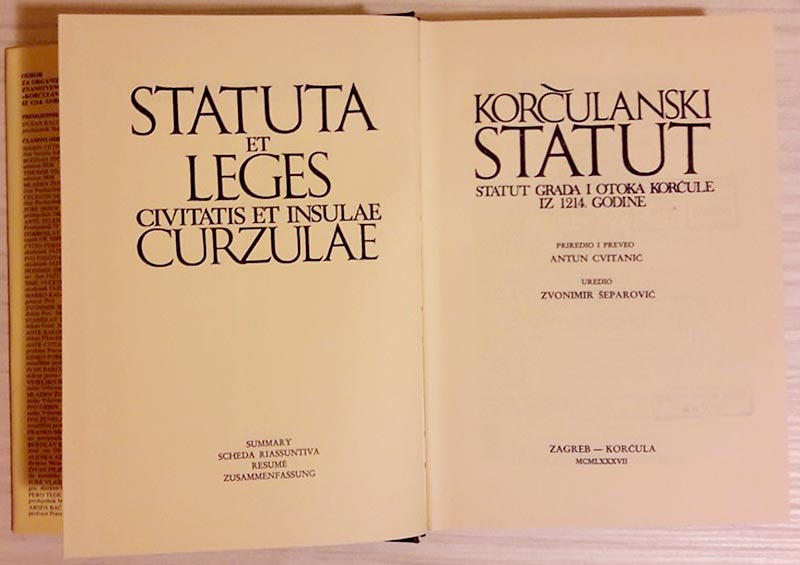

The Yugoslav (at present Croatian) Academy of Science and Arts in Zagreb, the oldest South Slav institution of its kind, aware of the great cultural and historical significance of this Statute, published the text of the Statute of Korčula, starting this with the publication of a series of South Slav (in fact almost all Croatian) legal and historical records (Monumenta historico-juridica Slavorum meridionalium). J. Hanel, professor of legal history and a full member of the Academy, edited the text entitled STATUTA ET LEGES CIVITATIS ET INSULAE CURZULAE, which was published as far back as 1877. It contains later amendments and changes introduced in the Statute up to the middle of the 15th century. All this is given in the form of a reprint in this book, with the translation of the Latin text into modern Croatian and an Introduction.

Popular Routes: Split to Korcula, Korcula to Split, Dubrovnik to Korcula, Korcula to Dubrovnik

The Statute of Korčula regulated all the legally relevant social relations in the commune of Korčula from the 13th to the 15th centuries, with the exception of those social relations which, even during this time, were regulated by common law. The Statute was to a certain extent applied also later, and even after 1420, when Korčula came under Venetian rule, which lasted several hundred years, i.e. until the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797. During this time, statutory regulations and their changes began less and less to reflect Korčula’s autonomy, becoming more and more an expression of the will of the central state authority of the Venetian Republic.

II.

The medieval commune of Korčula was engaged primarily in agriculture, i.e. farming and livestock breeding. Its population lived off the land, engaging mostly in wine growing, animal husbandry and forestry. It should be noted that the commune produced enough to cover its needs in livestock and wine, while it had to import wheat.

The Statute contains a number of regulations on this basic economic and social activity of the commune: norms on farming, especially wine growing; on agrarian-legal relations, livestock breeding, especially on relations between shepherds and their “masters” who entrusted their cattle to them to be taken to pasture; on forestry, especially the utilisation of wood and bitumen; on fishing trade; on local crafts; on financing, with special emphasis on various communal taxes. It also contains general information of food supply to the commune; on the defence of the town of Korčula and of the whole island; on what would today be called enforcement of law and order, as well as on the problems of town planning and building, and even on ecology.

Among these clauses, the most numerous are those on wheat trade, and in view of the shortage of wheat, on measures favouring its imports; on the wine trade, and in view of the large quantities of this product, on the prohibition of wine imports.

III.

The Statute also regulates the organisation of power in the commune of Korčula, the actual functioning of this power and the position of the Church in the commune. In reading the Statute we see that in the 13th-century joint decision-making was still practised reflecting vestiges of the former Slavonic clan system. Thus, when the people of Korčula signed a contract with Marsilius Georgij in 1265, all the inhabitants were said to have gathered at the general assembly of the whole community. In actual fact, though the situation may have been slightly different, i.e. it could be that only distinguished people and officials of the commune of Korčula took part in the assembly, the very mention of the whole community of the island in this context recalls the former equality and democracy, which existed under the difficult conditions prevailing at the time, and the daily struggle for survival.

However, with time developments led to economic differentiation, so in Korčula those who had greater wealth, and were besides respected as the descendants of the former clan chieftains, seized political power. This process was probably further accelerated by the desire of the people of Korčula to limit the social power of the hereditary Venetian governors (knezovi – comites) from the Georgij family. And thus the people of Korčula gradually came to be divided into two groups: the plebeians and the patricians. Instead of the former general assembly of the whole community, a new communal body emerged – the Great Council (Generale concilium) which at first included among its members distinguished plebeians as well, but later became predominantly and finally exclusively patrician.

After 1358, when the rule of the Venetian Georgij family ended, Korčula, together with the rest of Dalmatia, came under the rule of the Hungarian-Croatian Kingdom. The commune was headed by officials bearing the title of knez (comes), but this was no longer a hereditary title as during the Venetian rule, and they were no longer as powerful as before, since the Great Council took on an increasingly important role. In principle the Great Council wielded all the power in the commune, but in actual fact it retained only the legislative function and that of arranging foreign political relations with other communes. The legislative function of the Great Council consisted in passing various statutory resolutions with a majority of votes and including them in the communal Statute. Thus, the Council also edited that section of the Statute (see page 26 of the Latin text) in which mention is made of the year 1214. The purpose of this was probably to stress that, even before the arrival of Marsilius Georgij, Korčula had its own Statute, although some of the provisions which follow were meant to complement the previous ones while some were completely new. Bells announced the convening of sessions, and these were most often held in the town of Korčula, in the cathedral of St Mark, the patron saint of the commune of Korčula.

The Great Council decided about general norms which then were implemented by the Small Council (Consilium parvum) and most often by the part of the Small Council called the Curia (Curia) or communal administration (regimen). The Curia was made up of the knez (comes) and three major judges (iudices maiores). They, together with three minor judges (iudices minores), which are also called councillors (consiliari) to the Small Council, made up the Small Council. The implementation, i.e. the realisation of statutory provisions, in the everyday life of the Commune and its members means in fact governing on their basis and judging in civil-law and penal questions. These administrative and judicial functions were done so by the Small Council, or, in the great majority of cases by the very Curia. This was completely in accordance with the medieval organisation of authority were the same officials governed and judged, because the legal competence was not yet separated form the administration.

It must also be noted that Korčula, like Dubrovnik and other Croatian medieval littoral communes, did not have strictly centralised authority within the town walls. Thus, minor judges used, according to the Korčula Statute, tour Korčula villages very often and execute the legal authority.

The Church played a significant role in the legal life of the Korčula commune, as elsewhere at that time. Itself hierarchically organised, it adapted itself to the social changes and aristocratism of authority. Thus its bishop had to accept the provision of the Statute that he was not allowed to name as a canon any plebeian without the consent of the Great Council. However, as in other communes as well, there was some conflict between the Korčula commune and the Church. The example was in prohibiting the Church to inherit real estate and later abolition of that prohibition. The Church, as the inheritor of the Roman tradition, influenced definitely the formation of authority in the organisational and legal senses in many European countries and in Croatia, and thus also in Korčula.

The commune had a number of specialised services, such as for example the communal chancellery with a chancellor (cancellarius) at its head, the communal treasury with a treasurer (camerarius) and others. As the influence of the aristocracy increased, these services were reserved for the nobility, while the plebeians performed only the least important functions connected with agricultural activities, such as for example that of the field guard (poljar, polschich, pudarius – according to the Slavonic etymology).

IV.

The large number of statutory norms, different in content and presented unsystematically, can nevertheless be classified into the traditional legal fields such as the status law and family law, proprietary law, law of obligations with elements of the maritime law, inheritance law, criminal law and law of procedure.

The provisions contained in the status law show that the former equality had gradually disappeared and that a privileged class emerged, a clear division being established between the patricians and the plebeians. Vestiges of the slave trade can be observed in the provisions on the repression of the slave trade. The legal position of women is also interesting to note.

The provisions of the family and marital law give some indications about the way families were organised in medieval Korčula, about the relations between parents and children, husband and wife, etc. Christianity, i.e. the Catholic-ecclesiastical law, as well as the former Roman tradition on the island and the Slavonic culture of the people of Korčula – all these factors no doubt played an important role on regulating these relations.

As regards the proprietary law, especially the institute of ownership, one notes a considerable departure from the former Roman law, and thus like in other medieval judicial system the general notion of ownership no longer existed and every entitlement to proprietary rights belonging to others were not even mentioned.

It should be noted that the notion of possession (owning) in the sense of the former Roman law was not sufficiently developed in the medieval littoral communes, which refers also to Korčula. This means that a special protection of possession which would be independent from examining the right to possession, did not exist. Thus, the fact of disturbing or dispossessing of possession was not discussed exclusively, but one immediately raised the question of the right to possession.

As regards the law of obligations, one can note a tendency to regulate relations between creditors and debtors in such a way as to ensure that obligations undertaken by the debtor are fulfilled to the letter. In actual fact, economic progress of the commune was possible only provided there was a greater legal security and therefore such provisions of the law of obligations not only reflected improved economic circumstances, but also encouraged further economic progress. The strict penalties for false testimony and forgery, as well as the regulations aimed at preventing debtors from shirking their obligations bear witness to the commune’s interest in creating a certain amount of trust in commodity exchange. Of particular interest are relations pertaining to the law of obligations in farming and livestock breeding. These relations were not left to be spelled as the interested parties pleased, since many questions regarding these particular relations had previously already been defined by the Statute, which made them matters of public concern and showed how interested the commune was in ensuring the functioning of the economic activities carried out on the basis of these agreements.

Mention should be made of certain provisions of maritime law on coming to the rescue at sea. Of particular interest are those which prohibit the people of Korčula from buying objects or commodities obtained from shipwrecks. It was not out of compassion for those who suffered a shipwreck that such regulations were drawn up and that the former practice according to which inhabitants of coastal regions appropriated the remains of a shipwreck which were washed ashore was abandoned; it was rather because of the need to establish and maintain good relations between the communes, especially between those with ships at sea. Such provisions were, therefore, indispensable for further progress in maritime trade and for the economic development of the commune. The Korčula Statute anticipated with this solution some rules of today’s international conventions for several centuries.

The provisions regulating relations between the people o Korčula and aliens, i.e. those who did not belong to their commune, were meant for the same purpose. The main principle underlying these relations was that of reciprocity, according to which the people of Korčula had to treat aliens in the same way as the aliens treated them.

The hereditary law of the time seemed to contain clear elements of ancient Croatian, i.e. Slavonic law, by which it differed from Roman hereditary law. According to these provisions, both male and female descendants or relatives could be heirs, but men had priority over women of the same degree of kingship, in other words, men excluded women.

The criminal law in the Statute of Korčula stipulated punishments for particular acts considered to be a threat to the system of communal authority, to the prevailing ideology and to the life and activities of the people of Korčula. It is quite understandable that this law was mainly intended to protect the interests of the ruling class, and that whenever sentences were laid down particular consideration was given to the class, i.e. social position of the perpetrator of the crime and of the victim. In this respect, of course, there was no equality of all people before the law, but neither was there pronounced inequality such as that found in other more highly developed communities. The spirit of the former collectivism and solidarity of the Slavonic clan system was still present. It can be found for example in the vestiges of collective responsibility of the whole community in which the damage was incurred and in the remnants of ancient beliefs, according to which animals were held responsible simply because they had caused the damage. This can be observed in the linguistic formulations of punishment for any damages so incurred.

The commune as an organised political community prohibits self-help and calls on all the people of Korčula to refer their conflicts to the communal Curia, or else the Curia often without waiting for the interested parties to take the initiative resolved the problem. In such cases the Curia acted as a court, dealing with civil and criminal procedures. The statutory provisions on court proceedings are also pervaded by ancient beliefs, especially those regulating the hearing of evidence. Thus we find vestiges of former solidarity between members of a tribe and their fellow tribesmen facing trial. These were cases when a certain number of the tribesmen were allowed to appear before the court and testify in favour of the accused. What is surprising, however, are some formulations resembling the present-day human rights guarantees, such as for example the provision that no one can be sentenced unless he has been formerly asked to defend himself, and that no verdict either civil or criminal can be passed if it is contrary to the statutory provisions. At first glance, one might get impression hat these are ideas which several centuries later, on the eve of the French revolution, were to be further elaborated by he rationalists. However, the additional provision that in passing a verdict, the ancient, established customs should be considered, suggests that such formulations are more probably remnants of the ancient Slavonic clan and tribal solidarity and equality arising from the difficult and generally precarious economic circumstances of pre-state and pre-communal life.

V.

Owing to all this, the Statute of Korčula continues to arouse the interest of scholars and the public both in Croatia and abroad. It was printed as far back as 1643 by the Venetian Republic with a parallel translation in Italian, but this Venetian edition was mainly meant for practical purposes, which bears evidence of its continual use. A scientific study of the Statute was, however, undertaken at the end of the first half of the last century, and J.M. Pardessus in his famous work entitled “Collection de lois maritimes antérieures au XVIIIe siecle, I-IV, Paris, 1828-1845” included and stressed the maritime provisions, while the first legal and historical study was carried out by Gustav Wenzel and entitled “Studien über den Entwicklungsgang des Rechtslebens auf der Insel Curzola” in the “Archiv für Kunde österreichischer Geschichts-Quellen, Wien, 1849-1851”. A notable work, brought out more recently, is the book by V.T. Pašuto and I.V. Štal entitled “Korčula-Korčul’skij Statut, Moscow 1976” published by the Academy of Science of the USSR.

In brief: Scholars all over the world today are familiar with Roman law thanks to the Emperor Justinian’s codification of the law in the 6th century. It was on the basis of Justinian’s Code that the law under which the Romans lived continued to develop, especially the proprietary law and the law of obligations. The oldest code of the Slavs who, after leaving their original homeland and settling on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea, came into contact with the Romans, was the Statute of Korčula. This makes this 13th century Statute an unique record of the encounter of cultures, of symbiosis and interpretation of Roman and Slavonic legal elements, as can be seen from some Croatian words in the text otherwise written in Latin (as was the custom at the time), and particularly from the toponyms, some of which bear the names of ancient Slavonic deities from the period preceding Christianization.

The Statute has two main characteristics: a jealous preservation of tradition and Croatian identity, among other things by the struggle for the island autonomy, regardless of occasional conflicts between the plebeians and the patricians, and taking over and further development of those elements of the European law and legal thought which had been verified during history as best possible solutions for promoting economy and ever more harmonious social relations. And so, while the despotism of almighty feudal rulers domineered over the great part of Europe, although not specifically codified, the germs of constitutionality, to some degree of human rights and the market economy were generated in the Statute of the town and island of Korčula.

author: prof. Antun Cvitanić (Translated from Croatian: Živan Filippi)