Marco Polo and Korcula

Introduction

The city of Korcula, in the opinion of its many distinguished visitors throughout its rich history, is one of the most attractive and best-preserved towns from the Middle Ages in the Mediterranean area. The island of the same name is one in the long string of ‘pearls’ forming a great archipelago that runs along the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea; rightfully the pride of the Republic of Croatia.

Why the modern tourist at the end of the twentieth century (though not acquainted with the details with the rich history) is immediately conscious of the connection between Korcula and Marko Polo is an interesting question. Does the knowledge come merely from tourist slogans and publicity, or from a deeper sense of tradition and historical memory?

The Depolo family have lived in Korcula for centuries, proof of which exists in the numerous documents held in the Korcula archives; and one of member of the family the young flower decorator Mate Depolo happened to meet in 1993 another young woman girl who is a descendant of the Great Kublai Khan, They were both in Wells at the time under the auspices of the BBC. A hotel in Dalmatian style was built in Korcula in 1972 and named “Marko Polo”. The tourist agency “Marko Polo Tours” has also existed in Korcula for several years. Jadrolinija, the Croatian Shipping Line, gave the same name to its most beautiful and biggest passenger ship.

The first question which most visitors ask, while irresistibly attracted towards Korcula in a wish to escape for a while from the trials and burdens of everyday life, is “Where is the tower of Marko Polo”? Does not its position in the immediate vicinity of the St. Marko cathedral, in the central town square, together with the houses of many old noble families, confirm the Korculan origins of Marko Polo? If we add that the sculptor from Corinth, Polo, lived in Korcula in the 5th century B.C. (according to the Encyclopedia Treccani) and that Korcula at that time, according to Skylac, was the main Illyrian emporium in the Adriatic, then it becomes evident that the traditional hearsay about the Korculan origins of Marko Polo must have its ancient roots in history, which is in itself a kind of word of mouth tradition, and an attractive story. Moreover, the belief is also fed also by the oldest legend of all regarding the foundation of Korcula, which says that the town of Korcula was founded by the Trojan hero, Antenor, after the fall of Troy. While one old Venetian manuscript also points out that, together with Antenor, a certain Lucius Polus, arrived on the coast of the Adriatic Sea, as an ancestor of the family Polo.

In 1995 Korcula celebrated the 700th anniversary of Marko Polo’s return from China to Europe. Korcula had also solemnly celebrated the 700th anniversary of his birth earlier in 1954. Within the framework of celebrating the 700th anniversary of his return from what was then far away though today much more accessible China, the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (HAZU) held a scientific symposium under the title “Marko Polo and Korcula in the 13th Century”. Concerts, exhibitions, lectures, boat parades, commemorative stamps, seals were organized and produced, and the house of Marko Polo is now being rearranged in the style of his voyages and happenings. A special attraction is a popular song about Marko Polo on disk. This arrangement by the best Croatian pop singers was sent to radio stations all over the world under the title “Seven Hundred Years”. One verse in that song speaks about the bright star high in the sky which was guiding Marko Polo during his life-long voyages. this was the North Star, his star of the North Pole, mentioned several times in Marko Polo’s book Million.

The purpose of this commemorative work is not to prove that Marko Polo was born in Korcula, though it every Korculan small child feels instinctive that this is so. Even less is its purpose to challenge the undisputed role of Venice in the life of Marko Polo and his family. After all, Korcula was for many centuries under the government of Serenissima, which is to be thanked for the rising prosperity of Korcula in the 14th and 15th centuries. The real aim of this book is to present to the interested tourist all that connects Marko Polo with Korcula and at the same time to emphasize the significance of his interesting voyages and discoveries when he ventured to unknown worlds.

Marko Polo is the property and inheritance of the whole world. His life story still speaks clearly to today’s man about the richness of various ambiences, races and cultures, and about the instinctive wish of every well-intentioned inhabitant of the Earth to know the world around him, to get more contact with other people, and live his life in an interesting way in friendly relationships with others and not against them. Exactly as did the first world traveller and writer, MARKO POLO.

Korcula and the Polo Family

The 13th century was the time when Europe lived in constant conflict between its town-states, which were still preoccupied with the Crusades. It was a time when numerous armies were crossing European soil, destroying foreign towns and killing off their inhabitants. This was a time of poor living conditions, when food and clothing were lacking, and when European inhabitants did not know much about raw materials and agricultural skills. They had no knowledge of coal, oil, paper, gunpowder, compasses, coffee, potatoes, corn, tomatoes, tabacco…all the things without which the life of contemporary man would seem inconceivable.

Popular Routes: Split to Korcula, Korcula to Split, Dubrovnik to Korcula, Korcula to Dubrovnik

But while political instability and economic poverty were limiting the life of the average European, reducing it to pure survival, the stability of the Roman Catholic Church – in spite of all dynastic struggles and doctrinarian rigidity, often with perilous consequences – at the same time opened to him spiritual perspectives, giving hope and laying down the structural base for cultural development. This was the time of the most splendid Gothic building, as for example the cathedral of Chartres, begun in 1294; of Reims in 1210; of Salisbury, erected in 1220. One of the most significant political events was the proclamation of Rudolf for Holy Roman Emperor, who managed to spread the influence of the Habsburgs to Austria, thus laying the foundations of the state which would, for the next five centuries, represent the bulwark of European culture.

In that interplay – of the material and the spiritual, of violence and reconciliation, a mixture of awareness and dream – a unique position was to be held by that small Italian town-state, called Venice. Built on an island archipelago, near the mainland, it looked like an enchanted vision which emerging like Aphrodite from the Adriatic Sea. But Venice was not an apparition. Built-in stone in the magnificent style of the Middle Ages with emphasized Byzantine elements and connected by a network of channels and bridges, it manifested the power of a trading and maritime force, spreading its influence across the Adriatic aquatic surface, and over to the Mediterranean as far as Constantinople itself, which fell into its hands in 1202.

The town and island of Korcula were unprotected, and indeed there were many who fought for it at that time because of its strategic position on the maritime trade routes and also because of its geographical configuration which makes it ideal for the refuge of warships and merchant galleys. For these reasons, Korcula was unlikely to escape the powerful arm of Venice. The Croat population of the island and the town of Korcula tried hard to resist the intentions of the Venetian Republic. In order to hinder Venitian plans and protect their island community, the Korculans adopted their communal statute in 1214. That statute, the oldest legal document in this part of Europe, codified the whole life of the town and the island and, in many of its decrees, set an example of the European proportions. Numerous decrees regarding maritime law, the abolition of slavery, the protection of the environment etc. witness to a high political and cultural level in Korcula at that time; though it was living as were other Dalmatian towns in the 13th century as well, in the danger due to the avaricious appetites of the powerful forces around it. The Korcula statute protected Korcula from the authoritarian reign of Venice, but at the same time offered Korcula Venetian protection from other possible aggressors as it wanted to continue its relative prosperity, especially in shipbuilding, stone-cutting and shipping. The citizen of Korcula, though under the yoke and protection of Venice could guard his rights and his lifestyle from the outside world because of the legal codex, but he wished to look beyond the borders and the limits of western metaphysics and he began to broaden his aspirations to take in the outside world, for the fulfilment of his dream regarding a better future. His sailing ships ventured in search of the unknown and, by reason of their masculine violence ploughed the Mediterranean furrows, whereas the citizen himself remained in the secure maternal womb of his city nucleus and his peasant field. Sea furrow, field furrow, and a furrow as the line of his writing, welded in the Korcula statute, spelt for the Korcula citizen the chance of a wondrous joy of existence.

Amidst the overall risks of the European insecurity, Korcula, either by force or willingly, accepts the previous duke of Dubrovnik, Marsilie Zorzi, a Venetian nobleman, as its duke in 1254. In that same year, Marko Polo was born.

The Polo family is much respected in Korcula; living over centuries in the town of Korcula. It produced over the years numerous shipbuilders, smiths, stone-masons, tradesmen, priests, and public notaries. Marko’s father Nikola and uncle Mate founded their trading outpost in Korcula, and the members of the Polo family were guardians of the walls around the town of Korcula. But, for the skilful tradesmen Nikola and Mate, Korcula was only the starting point of their business trade and their adventurous life. Marko’s father and uncle penetrated deeply into Asia. They erected a tower and founded their own trading outpost in the town of Sudac on the Crimea. They had their main trade centre in Constantinople, to which many Korcula businessmen and shipbuilders were travelling and for some time they were living there. Mate and Nikola Polo traded successfully with the Persians. They were cognizant with the secret ways which led through Syria and Iraq as far as the coasts of the Persian Gulf. They also knew the areas where the precious pearl oysters could be found. Wherever they ventured they were made welcome as people who were “noble-minded, wise and reasonable”. They knew the routes that led to the fur traders of southern Siberia. They had trade contacts with the dignitaries of various Tartar peoples, and they reached the court of the Great Kublai Khan in China. They had started their journey before Marko Polo was born. The successful Korcula tradesmen feeling secure in their centuries-old native soil of Korcula, left their family and still unborn son Marko, as they gazed towards the Far East searching there for a realization of their dream of the rich life. Their ideas of fusing the cultural structures of the West and the East also decreed the destiny of Nikola’s son, Marko Polo, from the day of his birth.

Marko achieved the usual education of a young nobleman of his age. He learned a lot about classical writers, he understood the text of the Bible and knew the basic theology of the Roman Catholic Church. He spoke French and Italian, especially the trade vocabulary, and was skilful in keeping business books. The Church books and songs in Croatian from Marko’s time have been preserved in Korcula, and it is most probable that Marko knew the Croatian language as spoken by the inhabitants of Korcula. That knowledge was to help him very much when he traveled with his father and uncle across south Russia, then inhabited by Slavonic tribes and under Tartar reign. The European languages which Marko learned in his youth were to be the basis for the development of his polyglot talents when he came in touch, in the Far East, with Chinese; this, too, he learned successfully.

Korcula first had a bishop in 1300, which contributed a great deal to the writing and maintenance of the archives, both Church and secular, and some well-known families kept their own archives. Thus, the always rich Korcula tradition passed on by word of mouth, received also written support for the preservation of the collective communal memory, thus giving birth to capable men ready for the adventures of body and spirit in distant worlds.

The oldest written document in which the Polo family is mentioned is a deed of gift dated March 14th 1400. The then Duke of Korcula, Mihajlo Musi and three Korcula judges donated to a certain Joannis a building in the town quarter on the eastern side, near the house of Bogavaz Dupolo. It is the exact location of the present “tower of Marko Polo”; from which one can see clearly all the Peljesac Channel; the route of trading vessels from Hellenic times to the present day.

A somewhat older document, from 1430, speaks about the life and work of members of the Polo family in Korcula in the 13th century, mostly featuring the centuries-old tradition of building Korcula style wooden boats, well known in the whole of the Mediterranean. That document is to be found in the private archives of the Kapor family in Korcula. In this, Mate Polo applies to the community of Korcula for a piece of land for his ship-yard, near the place where his grandfathers were building boats. That document is concrete evidence that the Polos were living in Korcula and building the boats even before Marko Polo was alive. Korcula shipyards were situated both on the eastern and western shores adjacent to the fortified medieval town. In this way, the shipbuilders, working in the vicinity of the city walls, and living inside them, were able to defend their town in case of enemy attack. In the list mentioning ship-builders in 1594, there are 16 ship-wrights from the Polo family, and in the 1810 list, 22. From a legal case of 1778, we learn that the name of the owner of a shipyard in the eastern suburb was Marko Depolo. As the skills of shipbuilding, as well as the ownership of the shipyards, were passing from generation to generation, from father to son, various families were for centuries using the same plots for the needs of their workshops. It is evident from the land-registry maps of the past century, and from photos exhibited in the City Museum that Mihovil Depolo, Nikola’s son, (1864-1943) was the owner of one of the bigger shipyards on the eastern side (“Borak”) and that Lovro Depolo (1853-1943) was the owner of the biggest shipyard of all on the western side of the town of Korcula (“Sv. Nikola”).

The Korculans were not only outstanding shipbuilders but also experienced seamen. They excelled, too, as good warriors in many sea battles; among them, members of the Depolo family. Archive material and memorials confirm that the duke of Korcula, Andrea Zane, in 1584, entrusted, among others, Jerolim, Pavle and Nikola Polo, with finding crews for the participation of the town of Korcula in one of the sea battles.

Archive material concerning Korcula reveals also the rich religious life of the Korcula people especially notable in the founding and regular activities of the brotherhoods. These offered, to the various groups belonging to specific crafts, a spiritual refuge and place of relaxation from everyday hard work. Like others, the Polos lived an intensive religious life. Bishop of Vinzenza, Mihovil Priuli issued a charter on January 28 1603, for the founding of the brotherhood of St. Michael (Sveti Mihovil). Among the founders, were listed the names of Pavle, Marko, Jakov, sons of Dominik De-Polo, and Vicko and Ivan, sons of Nikola De-Polo. The name of the Franciscan procurator (representative), Marko de Polo, was inscribed on the apple of the silver carrying cross belonging to the Franciscan monastery founded on the island of Badija, near Korcula. The cross was the work of the Sibenik goldsmith, Dobrosevic, whose name was also inscribed on it. The altar painting of St. Ann in the church of All Saints, dating from the beginning of the 17th century, reveals in the text at its base that the painting was the gift of Vinzentie de Polo, presbyter Marko de Polo, and others.

If we walk through the cemetery of Korcula we can see numerous tombs of the Depolo family, dating from the founding of the cemetery to the present day. Outstanding for its beauty is the family vault of Nikola and Rosa Depolo from 1891.

The surname Polo derives from the name Pavao. It was first mentioned in its Croatian form Paulovic (Pavlovic), then in the Latin form De Paulis, Venetian Di Polo, and afterwards remained only Depolo. The earliest mentioned medieval Identification System was the first name and, beside it, the additions, which specified the particular person, differentiating it from others of the same name. The surname appeared only when one of the additions to the name became hereditary. The confirmation of this rule, and that in the case when the surname Polo derives from the name Paulus (Pavao), is found in the following example. The public notary, Jakov Giricic, drew up a will for the ship-builder Paulus (Pavao) in Korcula on February 1st 1565. His surname is not mentioned, only his first name. The original of that will is now kept in the Historical Museum in Dubrovnik. It is evident from other documents written after the said will (contracts, wills and registers) that the sons of the testator now bear the permanent surname, De Paulis. The grandson of the will-maker, Nikola, bears the surname Di Paulo, and the great-grandsons, Ivan and Vicko, whom we find among the founders of the brotherhood of St. Michael, bear the surname De Polo.

Frequent use of the surname in its Croatian form of Paulovic (Pavlovic) is evident from a review of the registers between the 16th and 18th centuries. It is last time mentioned for the February 2nd 1747 when Margarita, daughter of Ivan Paulovich and Vica Foretich, was born. The form of the surname Depolo became common with the birth of Mihovil, son of Marko and Palma, on June 18th 1771. From that time it has been listed in this form only. There is an interesting case of the brothers Marko and Andrija, of whom each uses another form of the surname. The contract made in 1525, between the Korcula builder, Marko Pavlovic and the Korcula chapter house, states that Marko obliged himself to complete the building of the northern aisle of the cathedral in Korcula. However, he died during the building in 1532, and his brother, the priest Andrija, with the surname De Paulis was proclaimed the tutor of his children.

712 persons with the surname Polo-Depolo were born in the period between 1583 and 1946. Domenego di Polo, god-father at the baptism of Vinzenza Ismaelis on June 26th 1583, appears on the very first page of the first registry of births in Korcula. The most impressive survey of the expansion of the surname Polo-Depolo is the list of priors (“gastaldi”) of the brotherhood of St. Roko, founded on August 16th 1575. A review of the archives of Dalmatian town-communities reveals that the members of the Polo family, later Depolo, have lived continuously in the town of Korcula for centuries.

With regard to Italian professional literature, the most frequent opinion is that the Polo family comes from Dalmatia. Such a claim is evidenced in the manuscript chronicle about Venetian history covering the history of Venice from its beginning until 1446, and also in the book Le vite dei dogi (The Lives of the Dukes), published in Venice in 1522. The same thesis is expounded in later Italian literature, as for example in Biografia universale antica e moderna from 1882 and Storia di Venezia from 1848.

Today, there are Depolos living outside Korcula – in Dubrovnik, Split, Rijeka, Zagreb, Athens, Ismir, New Zealand, USA, Chile and Argentina. All of them originate from Korcula and have family connections with their Korcula relatives.

All the facts mentioned lead to the conclusion that Korcula is the town of the Polo family – Paulovic (Pavlovic) – De Polo – Di Polo – Depolo g continuously in the period from the 13th century, and according to verbal tradition even much earlier, until the present day. At the same time, Korcula is the town from which many members of this family have gone to other towns and other countries. Some of them return and some of them spend their whole lives in the new environment. If the above-written documents, especially those printed in Venice, say explicitly that the family of Marko Polo comes from Dalmatia, all available historical sources confirm that Korcula is, without any doubt, the town of origin of the family called POLO – DEPOLO.

The centuries-old oral tradition – handed down by word of mouth in songs, proverbs, stories, legends – connects Marko Polo and Korcula; in the development of writing, the organization of authority, education, and culture. This cedes place gradually to written evidence in the form of archives, manuscripts, contracts, deed of gifts, registry of births, deaths and marriages, and, in the recent times, in the form of literary works. So the legend of Marko Polo expands ever further, and more and more it is taken over by visual and written media: television programmes, expert and popular periodicals, tourist reviews, and set books all over the world. Marko Polo and Korcula become an inseparable structural pair in which each pole enriches and ennobles the other.

Million – a Wondrous Book about the Wonders of the World

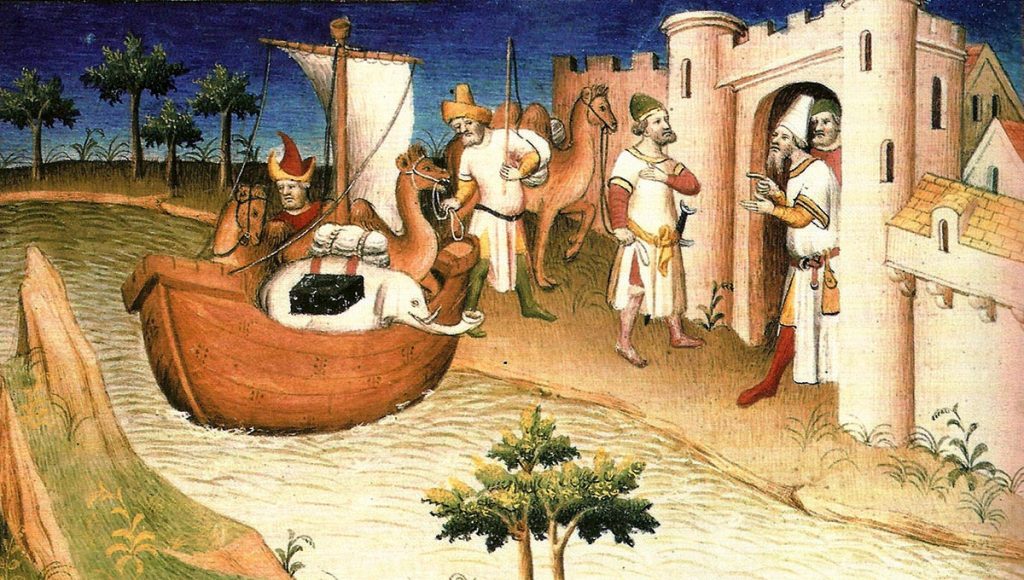

Marko Polo described his voyage and his life cycle in the book Million in the French language, which he dictated to a writer of knightly romances, one Rusticiano or Rustichello from Pisa, while in the Genoese prison after the battle off Korcula in 1298.

Marko Polo manifested in this book his undisputed talent as a great storyteller, inquiring traveller, a connoisseur of various races and culture, historian, cartographer … The original title of the book “Description of the World” speaks about Marko’s ambition that his book becomes an extensive cosmography, a complete account of the then-unknown biggest continent – Asia. It is “one of the greatest books of all times”. Marko’s descriptions and remarks are very objective and self-reticent.

The notes, which he was jotting down for more than 25 years, served him well in presenting in detail the great variety of customs and people, of which many are bordering on the fantastic. His cultural approach to various races, peoples, and religions is, for the thirteenth century, outside any of the established canons. He was always impressed by beauty – of woman, character, landscape.

The narration of the book follows quite closely the real voyage of the Polos, but it branches often into descriptions of places which he had not visited himself but about which he heard from his friends. Typical digressions are those about Mesopotamia, the Assassins and their castles, Samarkand, Siberia, Japan, India, Ethiopia and Madagascar. The basic structure of the book is a quest for the Grail. The hero of medieval romance, in this case, one young Venetian and Korculan, Marko Polo, goes in search of the faraway worlds and for exciting adventures which will reveal his talents, bring him glory, eventually to return in his orbiting cycle to the place from which he started his voyage.

Million – a Long Voyage

It was in Venice in 1269 that the Polos settled after Marko’s birth. When Nikola and Mate Polo returned after fifteen years of trading in Asia back to Europe, Marko was fifteen years old and his mother had died a long time previously. Marko listened with enthusiasm to their stories about the wonders and riches of China. His joy knew no bounds when he learned that he was going with them on the next journey. In the summer of 1271, Marko, at the age of seventeen years, embarked with his father and uncle on the galley and gazed with melancholy at the contours of Venice which he was not seen for twenty-four years, but he would be seeing more of the world than any man of his time. Navigating along the eastern side of the Adriatic Sea – the usual route of Venetian galleys in the Adriatic – Marko passed near his native Korcula, where he probably stopped to greet numerous relatives, and near which he was to pass again in 26 years time. No sea monsters, in which medieval travellers believed, appeared on their journey across the Adriatic Sea and the Mediterranean, neither did the pirates who usually threatened Venetian boats. After a fey days voyage, the Polos espied the fortified walls of Acra, a Palestinian stronghold, which was fortified by the crusaders and where pilgrims stopped on their visit to the Holy Tomb in Jerusalem. Walking inside the walls of Acra Marko gazed in wonder at the spires and palaces, as well as at the richly clothed noblemen.

His dreams about the heroes of the knightly romances became a reality. Then the Polos went to Jerusalem to satisfy a request of Kublai Khan to bring him holy oil from Jesus’s tomb. The Polos were just preparing to continue the journey when a messenger caught up with them and brought them the good news. Their longtime friend, the pope’s legate Theobald was proclaimed Pope Gregorius X and was waiting for them in Acra. Despite his great authority, he could not satisfy the request of Kublai Khan to send him a hundred friars to help him in the education of his people. He gave them only two Dominicans, but they escaped and asked for the protection of the templars when they heard that Mamelucs, previously slaves and now the masters of Egypt, were ravaging their way towards them.

The Polos had already loaded their ships with their main equipment, particularly with big quantities of quartz, when they heard about the serious wars in the region of Iraq. So then the trading group continued their voyage by land towards Asia Minor, and then to Turkmania (present-day Anatolia), which was famous for its beautiful carpets. Marko, until then, had only heard about flying carpets in the romantic stories told him at bedtime, and now he had the opportunity to see them in their fascinating colours and touch them by hand.

The Turkomans were citizens of the Great Khan, and Marko was especially impressed by their tolerance. Everybody could worship any god or religion, as long as obeyed the laws. That was great news for Marko and a pleasant surprise, as there was a great religious intolerance in Europe in his time.

The Polos small caravan would sometimes join a bigger caravan, and so they proceeded towards Armenia. Marko was enthusiastic about Mount Ararat, at the foot of which they slept, as it was the resting place of Noah and his ark.

They then went towards the southwest and entered Zorzania (today’s Georgia). Marko saw there a geyser which jetted out a big quantity of oil, which he said was used for firing candles and for curing rash. Marko, as a typical European of his age, did not know that the Egyptians, Romans and Persians had used oil for lighting, heating and even for impermeables. Also that the Chinese had learned to drill oil wells 200 years B.C.. With their bronze drills and bamboo panellings, they penetrated more than one thousand metres deep. However, Marko was among the first in the western world to report that these were deposits of oil in the region of the Caspian Sea.

Marko mentions the Nestorian Christians who were scattered all over Asia and were spreading the Christian doctrine which averred that Christ has two natures: divine and human. This was unacceptable to the European Catholics of that time, who considered that Christ had only a divine nature. However, the Nestorians had founded their Church in China A.D. 638, almost a thousand years before the first Jesuit missionaries started to come there. Marko was to mention them later many times. They got their name from the bishop of Constantinople, Nestorius, who was deposed as a heretic in A.D. 431.

Next, Marko describes Baghdad, the most romantic and mysterious town of the East, although it is not quite sure if he visited it himself. He told the story of how the Khan of Levant occupied Baghdad in 1258 and how he captured the khalif of Baghdad and asked him to eat gold, which he had amassed in enormous quantities on account of his soldiers’ wages.

Travelling at the average speed of ten miles a day, the Polos reached the Persian town of Saba (southwest of present-day Tehran). Marko was sightseeing and showed great interest in the magnificent holding the bodies of the three kings who had gone to Bethlehem to bow in front of the newborn Christ. Their beards and their hair were still intact. While in Saba, Marko also visited the sect of the admirers of fire, who were followers of the ancient Persian religion founded by the teacher Zoroaster. Marko explains the origins of that religion by expounding the allegorical story about the box which new the born Christ gave to the three kings. There was a stone in the box, but as they did not know its significance they threw it away. The stone transformed itself immediately into fire and flames. The kings took some fire to their homes, worshipped it as God and offered sacrifices to it. Fire as the symbol of new birth and purification is used in many ancient religions and pagan rituals. In the Catholic liturgy, a new fire is connected with the rebirth of Jesus Christ. It has become the anthropological archetype which connects many races and cultures, and it is used often in literature as the structural principle of narration which opens up new visions and adventures to the literary hero. Marko Polo realized the importance of fire for ancient religions, and he uses its description in his story own as well.

Nikola and Mate Polo, together with Nikola’s son Marko, came to Kerman, the town known for its spears, swords and other tempered arms made from fine steel, and also for its fine laces depicting various birds and animals, which was woven by women. Climbing cold mountain peaks over three thousand metres high and descending into warm valleys, Marko had the opportunity to see animals in the form of oxen with a hump and a kind of sheep which had a tail of more than fifteen kilos. After they had joined a bigger caravan, they experienced an attack by the wild tribe of Karauns amidst the dusty mist. Marko heard stories of how the Karauns conjured up dust on purpose by means of their diabolical chants. The Polos managed to escape from these wild tribes, but they decided to make the rest of the journey by sea. For that purpose, they went to the port of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf. Unlike the poor Iranian plateau, they found themselves in a land full of dates and parrots. They met tradesmen who were offering spices, pearls, linen embroidered with gold, ivory tusks and other goods brought from India. There was such unbearable heat in Hormuz that people spent their whole morning in the nearby river, protecting themselves from the sand which was brought by the wind. Marko heard how that wind, the “simun”, has such a tremendous force that it once suffocated the entire army of an enemy which was marching towards Hormuz. The bodies of the soldiers became so fragile that they crumbled into dust. Although Marko’s story is incredible, the travellers after him confirmed it. However, when some of the passengers saw the ships in which they had to sail further on towards the Indian ocean and heard about the storms which raged there, they lost any wish to proceed by sea.

They returned to Kerman and from there they went by the famous Silk Road, along which all trade with China was travelling. That was also the way by which Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity were spreading. On their way, they faced immediately a great desert full of poisonous green water. After a few weeks spent in the desert, they reached Tunocain in which the “most beautiful women in the world” lived. Or perhaps it only seemed so to Marko after such difficult days in the desert!

Marko was even more impressed by the story about the sect of Assassins who spread a horror over a large part of Asia for more than one century. Their ruler was the “Old man from the mountain”, who build a fortified castle in the mountains of Persia, south of the Caspian Sea. He arranged gardens of exuberant vegetation, fruit trees, flowers and fragrant bushes and murmuring streams. Luxurious pavilions were built around the gardens equipped with attractive paintings and rich carpets. Streams of wine, honey and pure water flowed there, and each of the magnificent houses was the residence of the most beautiful girls, skilful in dancing, singing, making love and playing on various instruments. The great master gathered there strong and bold young men, whom he drugged by drinks of hashish. When they woke up from their paradisiac dreams they believed that they were in paradise itself. Then the Old man from the mountain would ask them to kill his political opponents and promised to return them again into the paradisiac valley if they executed his cruel ideas. As they fulfilled all his tasks without objection, the word started to spread that the Old man had divine power. Among other great personalities, they killed the Persian shah, Grand Vizier of Egypt, two caliphs of Baghdad, several leading crusaders and many outstanding rulers. Only the Mongols, after three years of laying siege to the castle and after killing their ruler, managed to annihilate that dangerous sect of killers, who, like the heroes from medieval romances went in quest of the Grail, that luxurious paradisiac garden of pleasures and delights. Marko told in detail that wondrous story which so excited his romantic and narrative imagination.

From Tunocain the Polos went towards Balkh, in northern Afghanistan, where the trade routes between West and East cross. Balkh was still lying in ruins after Genghis Khan had destroyed it completely in 1222. Then, after twelve days journeying they came in front of the mountain chain where the precious white salt was extracted. Behind the mountains lay the province of Badakhshan, famous for its mines of rubies and sapphires. The clever king of that province restricted the digging of rubies in order to keep up their value. Marko describes shortly his year-long fever which he cured by changing the air and by staying in the mountains.

After Marko’s recovery, the small caravan of Europeans entered the valley of Kashmir, of which Marko says that it is full of shamans who practised black magic. Marko met these shamans later at the court of Kublai Khan.

Continuing their way towards the southeast, our travellers climbed the lofty Pamirs, where three big mountain chains meet, which the local people call the Top of the World. Among the wild animals that Marko noticed there, were huge sheep with curled horns more than one metre long. That ‘king’ of sheep later got a Latin name in Marko’s honour, Ovis poli. The mountains were more than 5,000 metres high so there were no birds at their peaks. Marko noticed that the air was so diluted that fire gave less heat and they could not cook their food properly.

The caravan reached the ancient town of Khotan, well-known for its deposits of semi-precious stone nephrite of various colours, from which many decorative objects were made. The travellers were following the southern arm of the Silk Road and thus came to one of the biggest deserts in the world, Takla Makan (in present-day Sinkiang province ). There were twenty resting places across the desert, but the water was rare and not always drinkable. Our travellers were finding human and animal bones, which laid the foundation for many fearful stories about that big desert. Marko used to listen with great interest how some passengers would sometimes lag behind their caravan and then start to hear voices and see the false figures of their fellow-travellers. Sometimes they would hear music, singing or the clasking of arms. That would lead them in a completely different direction from the caravan, and often to death. Although at the time many people did not believe in Marko’s stories, they proved later to be true. The sounds heard by straying travellers came from the falling of sand heaps among the dunes, so that these regions are called “sand which sings”. The visions are created by waves of heat and because of the parched thirst of the travellers. Later they were called mirages.

Marko’s prose is given poetic beauty by the mixture of dream and waking, reality and imagination, probable and improbable, explicable and inexplicable. Marko’s narrative technique became a model for many writers who did not have the opportunity to experience such interesting adventures as Marko Polo did.

After thirty days of travelling through the desert, the caravan of the Polos arrived in the town of Shachau, which means in Chinese “sandy region”, situated in the province of Tangut and belonging to the Great Khan. This fortified city was founded in the seventh century by the first emperor of the T’ang dynasty. Although the Nestorian Christians and Saracens lived there, the majority were “idolaters”, as Marko called them. They spoke “unusual” language, made a livelihood from agriculture, and they are bad tradesmen. They built a great number of monasteries and churches full of idols, to whom they worshipped and offered the sacrifices. As a way of baptizing their children, the idolaters killed a large ram offering it to the idol with great ceremony and praying for the well-being of their children. “If you will believe them” – as Marko says – the idol will feed on that meat, while a part of that meat the idolaters took home. The idolaters also offered similar sacrifices in food to their dead before cremating them. The family of the dead would build a small wooden hut, swathed in silk and gold, on the path leading to the place of burning. When the funeral procession passed by that hut it would stop there, and wine, meat and other food would be brought out, “all that in the conviction that the dead person would be paid the same attention in the other world”. The relatives would wait for the procession to arrive at the place of burning with prepared figures of people, horses, camels, and with small round pieces cut out from parchment in the form of golden coins, putting them on the fire together with the body. Because they believed that the deceased would, in the other world, receive as many servants, cattle and “soldi”, an equal number of parchment substitutes were burned together with them. Before the burning, the astrologers were invited and informed of the year, day and hour of the birth of the deceased. After the astrologers had determined under which constellation planet and sign the deceased was born, they proclaimed the day on which he should be burned. The body was kept, until that day, in the house and in a coffin of thick and nicely coloured plates. To prevent decay they put camphor and spices in the coffin and filled the fissures with tar and lime. They laid a table with food in front of the deceased because they believed that his soul came every day to eat and drink. When the day determined by the astrologers arrived, the deceased was ritually burnt with the greatest honours.

Marko Polo depicts faithfully the ceremonies of burning the dead, although he does not believe very much in their utility. Later anthropological investigation found that the ceremonies of burning the dead have been known in many civilizations without regard to the level of their development. Fire destroys the material part of the victim, purifies it and liberates it from its material chains in order that its soul comes in contact with the gods. It transforms the material properties of man into immaterial essence, making him closer to the divinity and opening the door of heaven for him. The Sicilian philosopher Empedoclo, who proclaimed himself god while alive, is said to have jumped into the fiery crater of Etna in order to confirm his divine mission. Although Marko Polo, as an educated Christian, speaks with an ironic smile about the idolaters who believe in more gods, he notices exactly the role of fire in the rituals of the so called primitive peoples. By means of the phenomenism of fire and the ritual ceremony of eating they incorporated themselves into the eternal circle of birth, dying and rebirth and thus gave sense to life on earth.

Marko’s travels continued along the mountains of Karakorum and diverged a little towards the south, where Marko admired the unusual ox yak and musk bull. When the Polos were at a distance of forty days from their goal – court of Kublai Khan – his escort waited for them and lead them to his magnificent summer residence in the town of Shangtu (in Chinese a “higher court”). Thus they made the last stretch of their great journey into the unknown in royal style. Marko was excited by the splendour and magnificence of the royal palace with its marble walls with gilded rooms and the exceptional paintings of people, horses, wild animals, birds, and trees. The palace was situated in a park enclosed by a twenty kilometre long wall. The Khan kept their a stud of 10,000 white horses and mares. The milk from the mares served the Khan and his family for drinking. A special tribe kept the horses, but nobody else was to drink the milk when the Khan was in his summer palace. The Khan stayed there during the summer heat only, and then he toured other big towns in China. While looking at the beautiful palace in Shangtu, Marko was convinced that he had come to an exotic and rich land, where he would be able to devote himself, as would do his father and his uncle, successfully to trade.

The beauty of the Khan’s summer residence can best be illustrated by the verses of the English romantic poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He fell asleep one day in 1816, after he had read about the travels of Marko Polo, and dreamed a dream which he transposed into a poem the following morning. He called the park in Shangtu Xanadu. Kubla Khan

In Xanadu did KUBLA KHAN

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where ALPH, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice six miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

As Marko’s journey proceeded, there appeared more and more signs of prosperity. The land was cultivated. The Chinese population was on a high level of civilization and, although submitting to the Mongol military leaders, they kept their own customs. Although they lost many citizens, the Chinese remained different from their invaders. At that time China was struggling in a sea of troubles and disturbances. The Sung dynasty was peaceful and paid ransoms to various conquerors. When the eastern half of China fell under the Mongol reign, the emperor’s court moved to Nanking and then to Hangchou. That ruling dynasty raised Chinese culture and civilization to a high level but was unable to resist the strong attacks of Genghis Khan and his very bellicose successor, Ogodai. The southern dynasty of Sung fell just before Marko’s arrival in China. The Kubla Khan was preoccupied with strengthening his rule and he looked favourably at Chinese culture. Marko took note of the very efficient Chinese organization of society and heard about the many good deeds of previous Chinese emperors. The Chinese had an advanced feeling for belonging to the community and for the care of all members of society, distinguishing them from the simpler and tougher Mongols.

Marko Polo, although under the influence of his medieval western education which supported a social organization based on the mutually opposed poles: nobleman/plebeian, man/woman, native/foreigner, priest/faithful, physician/patient, landlord/shephard, divinity/mortal …, realized more and more the value of the Chinese idea of social and economic stability and common harmony. Marko was very much interested in religion and its customs. After meeting, on his journey, several groups of Nestorians, various tribes of idolaters, Muslims, he was enchanted in China by a variant of Buddhism, mahajana-budhism. He was impressed especially by their rituals with the multitude of priests or lamas. They used, while preaching, wooden or metal rollers with an axis, with prayers written on them. You could say that these were the forerunners of present-day TV invisible screens from which broadcasters read their text.

Marko’s caravan came to the very door of the Chinese capital, which was then called Khanabalik; this was the time of the Yuan dynasty.

Million – At the Court of Kublai-Khan

When the two brothers, Nikola and Mate Polo, this time together with young Marko, found themselves again in this big town, they went straight to the emperor’s palace where they saw the ruler in the company of a great number of dignitaries. They bowed in front of him with the greatest respect. The Khan ordered them to get up and expressed his great joy at seeing them again. They showed him the letters and the credentials which they had received from the Pope and they handed him, as they had promised, the holy oil from Christ’s tomb. Then the Khan saw Marko, who was by then twenty one years old and asked: “Who is that young and handsome young man?” “Your majesty”, replied Nikola Polo, “this is my son and your servant.” The Great Khan replied “He is welcome and it pleases me much.”

In the time of Marko Polo, Peking was a densely populated town. The tradesmen and the citizens of all possible professions had their own quarters. There was a special quarter for about 20,000 prostitutes, who were treated with respect because they were considered persons of social significance in a big city. The body guards of the Great Khan numbered 10, 000 people. Roads lead from the capital to various parts of China. Every region was properly noted in the official books, as well as the distance from Peking to every town and village of the empire. Marko was impressed especially by the Kahn’s courier service on horseback which could bring him information from the most distant part of the huge country in a few days. This was possible due to courier stations where both horse and horsemen were exchanged. In this way message could travel about 500 kilometres in one day. Besides the couriers on horseback there existed a postal service run by messengers. They would carry small objects from place to place along a system of roads. Every horseman and messenger would be given permission to pass in the form of a small plaque on which was written where he came from and in which direction he was going. When he reached one station he would show his plaque and take another which would serve him as permission to pass until the next station. Any mistake, and its maker, was revealed in such a way. According to Marko’s opinion there were 10,000 stations in China and at least 300,000 horses. He expressed his doubts in his book that Europeans would believe in these inconceivable numbers.

The fortified inner town was situated inside Khanabalik (Peking); here stood the emperor’s palace, halls and gardens. The walls of the palace were decorated with carved and gilded dragons and paintings of birds, animals and war scenes. The roof shone in the sunshine with its spectrum of colours: yellow-red, azure blue, green and violet. Not far from the palace was an artificial hill, about thirty metres high and more than a thousand metres in circumference. On it Kublai Khan ordered the most beautiful trees from all over the world to be planted. On the top of the hill, called Green mount, there was a magnificent pavilion where the Great Khan used to go to refresh his spirit. At the foot of the Green mount, there was a big lake in which all kinds of fish were swimming intended for the Khan’s table. The Khan’s four wifes were living inside the palace. Numerous concubines were also living close to the Khan in the palace, and about thirty would be chosen every year among the most beautiful girls from Kungurat, the province known for its beautiful women. The parents considered the choice of their daughter for the Khan’s concubine as the greatest possible happiness.

However, Marko was most impressed by the banquets of Kublai Khan, which were taking place in the halls for six thousand people. The Great Khan would be sitting on an elevated pedestal, and beside him, on an enormous table, was a big jar of pure gold filled with wine. There were also jars of kumiss and other drinks. Kublai Khan preferred kumiss which was prepared for him exclusively from the herd of white mares. As the Khan drew the vessel to his lips, musicians would start to play and everybody would kneel down until the Great Khan had finished his drink. When eating was done entertainers and dancers would amuse the guests until dawn.

The great annual spectacle was the Khan’s birthday, September 28th. 20,000 noblemen attended, all in golden habits, ornamented with jewels and pearls of enormous value. Another court celebration was the New Year. The Great Khan would receive on that day gifts in the form of gold, silver, precious stones and beautiful horses from the whole empire. Sometimes he would amass a hundred thousand horses. All were of white colour which was considered exceptionally lucky. Up to five thousand elephants would be in the procession, wrapped in silk linen quilted with golden filigree. After the procession, the rulers, noblemen, and high clerks would gather in the great hall. One of the dignitaries would stand on an elevated platform and cry: “Bow down and worship!”, and everybody had to bow until his forehead touched the floor. Then they would treat themselves with abundant food and drinks amidst great merriment.

The Great Khan was enormouly respected. Everybody coming within 500 metres from him had to lower his voice and behave humbly. If somebody had an invitation to the palace, he had to take off his shoes and put on white leadher slippers before he entered the palace. If he wished to spit he had to take with him a small covered vessel.

Marko was also fascinated by the method of heating. As the Chinese used to take baths three times a week in summer and every day in winter, the Mongols took on that habit from them. They therefore needed a big quantity of fuel in the form of “black stones”, which was burning, Marko says, from the evening until the next morning.

Marko describes Kublai Khan as a benevolent dictator. He wished his subjects, of whom the majority were peasants, to live a decent life. Kublai Khan was shrewd enough to express his benevolence not only as a trait of his character but as a useful principle as well. His own income depended on the destiny of the peasants. If storms, blight or locasts devastated their harvest, he would liberate them from paying taxes and give them corn both for sowing and for food. To secure himself from a period of dearth, he would store big quantities of corn when it was abundant. If a family experienced a disastre it would be given as much food and clothes as it had the previous year. Children without a family home were brought up in special institutions, and many hospitals were also built. His officials were distributing thirty five thousand dishes of rice and barley to those who needed it most. Such a policy was very distant from the Mongol scorn for the poor, and was closer to the then Chinese moral principles about help for the needy.

A very significant mark of Kublai’s efforts was the building of the Great Canal, which stretched from Peking to Hangchou. He also planted trees on both sides of every big road. Kublai Khan knew how to connect the useful with the beautiful. He encouraged the development of various sciences as well. So he built observatories for the astrologers and astronomers who were very much esteemed then in China. He also showed a great tolerance towards various religions, which was also not only the expression of his character but also a useful approach which prevented conflicts in the empire. He asked the Christian Bible to be brought to him for Easter and Christmas, which he would then kiss. He also worshiped Saracen, Jewish and Buddhist feast days. When asked why he did so he answered: “I respect and honour all four great Prophets: Jesus Christ, Mohamed, Moses and Buddha, so that I can appeal to any one of them in heaven.”

Marko liked to watch at the magician’s skills of the Buddhist lamas, who mostly came from Tibet. He says that they could stop storms, and he was most impressed when one of them made a vessel containing wine fly from the table into Kublai’s hand and back to the table again, after the Khan had drunk it.

Marko was advancing excellently in learning Mongol customs and military skills. He learned several Asian languages in a very short time and excelled in wisdom. The ruler of China noticed immediately his common sense, and was also impressed by his looks and behaviour. He ordered him to be his envoy in a province that was six months by caravan journey away from the capital. On his return, Marko described to the Great Khan all he saw and reported to him the work he had done for him. The ruler was delighted by Marko’s intelligent report and Marko Polo, after that time, enjoyed great favour and affection from the Great Khan. The ruler ordered that all must address him by the title “master Marko Polo”. So our great traveller remained seventeen years in the service of the Great Khan.

Marko gradually became one of the most devoted dignitaries to Kublai Khan. Realizing how much the Khan was interested in the customs of the peoples of his empire, Marko carefully noted all his observations and experiences so that the official reports were transformed into interesting stories. Unlike the legendary Sheherezade, who delayed her death with her story telling to the cruel shah, Marko Polo was achieving, by his report-stories, greater and greater respect in the eyes of his master and so he became a kind of court writer. But the Great Khan knew how to use other talents of the young Marko. He pointed out, in his descriptions, to the abilities of various provincial rulers, and their shortcomings, and provided the Khan with a knowledge of trade, geography and governing. The Great Khan used this as the basis for his policy for the controlling of the distant regions within the enormous area of his empire. So Marko visited Burma and Korea, and came to Tibet and India. Wherever Marko Polo arrived he found prosperous communities, each of them trying to make use of its economic advantages. As skilful businessman, Marko noticed the advantage of using paper money in some places. This was an entirely new thing introduced by Kublai Khan. He issued special banknotes made of strong thick paper which was produced by pounding the bark of mulberry trees. The paper was cut to the desired size, reliefs were impressed inside and the cliches were done. The banknotes were stamped in the imperial palace with special colours, diluted in red ink. This paper money could be exchanged for gold of equal value instantly. After five years all banknotes were withdrawn from use. As the buying power of money decreased over the years, so its value in circulation also decreased. Thus the Great Khan fought inflation. Paper money was used in the provinces which today comprise the regions of modern China, whereas the hunting peoples of the Siberian north and various tribes of the far away south used a more primitive way of paying, with snails for example. Marko, however, was not conscious of the epoch making discovery which consisted in the fact that money was printed. This had been known in China since the ninth century. But he was especially delighted to see on his travels that the Mongol rulers did not destroy Chinese culture. Not only did they not destroy the towns but they respected the imprisoned Chinese emperor and his main wife and gave him a palace. There they continued to live isolated but in luxury. The Mongols adopted the basic ideas of Chinese philosophy, which distinguished man from things, so that they were only killing their opponents if it was necessary for the achievment of their strategic aims.

Marko Polo arrived in Burma as the official envoy of Kublai Khan in 1278, one year after the big battle between the kings of Burma and Bengal and the Mongol army. He describes that great event which took place in the plain of Vochan. The Mongols were approaching that valley with 12,000 well-equipped horsemen to face a much bigger Burmese army of 60,000 horsemen and infantry-men and 2,000 elephants. When the Mongol soldiers saw the elephants they were so scared that they turned back and started to gallop to the rear. Then the Mongol captain had the salutary idea of making the horsemen dismount from the horses and tie them to trees in the nearby wood. His soldiers then started to shoot at the elephants hitting their vulnerable parts with numerous arrows, which was the Mongol’s favourite weapon. The elephants started to run away towards the wood with enormous noise, while the wooden “castles” on their backs, holding twelve to sixteen well-armed warriors, were falling down while striking the branches of the trees. When the Mongols saw that the elephants ran away, they mounted their horses again and began to chase the enemy. Then a fierce battle occurred. “Then might you see swashing blows dealt and taken from sword and mace; then might you see knights and horses and men-at-arms go down; then might you see arms and hands and legs and heads hewn off: and beside the dead that fell, many a wounded man, that never rose again, for the sore press there was. The din and uproar were so great from this side and that, that God might have thundered and no man would have heard it!” After the battle the Mongol commander took some elephants to Kublai Khan and from that time he always included them in his armies. Kublai Khan knew how to use them better that the Burmese king.

Marko’s second important mission took him to the province of Manzi. This was an independent province in southeast China, which Marko describes as the richest province of the Eastern world. Immediately after Marko’s arrival there Kublai’s general, Bayan, crushed its resistance to the Mongol force, forcing the minor king and his queen-mother to recognize Mongol reign. Both were spared their lives, and the new Son of heaven did not humiliate them. Marko tells of how the Queen only consented to give up the struggle when she heard that the commander of the Mongolian army was called Bayan-Hundred Eyes. Their astrologers had earlier predicted that the man with hundred eyes would bereave them of their kingdom. The city of Yangchou lay within the same province; it was one of the biggest towns in the province, and Marko served there as a governor. Is it because of Marko’s modesty that he speaks little about that town and nothing about his experiences as the governor?

However, with all his modesty and cautiousness he could not avoid mentioning the greatest event in which himself, Master Polo, and Masters Nikola and Mate took part directly. The Mongol army laid siege for three years to the rich silk town Sa-yan-fu (Siang-yang-fu) but did not manage to capture it because of the ditches filled with water that encircled it. The Great Khan himself was with the majority of his army in the vicinity of the town. Messengers told him that their siege could not succeed because the town received its victuals from the areas they could not occupy. But the Khan ordered them to find some solution. Then the two brothers Polo and their son – then already an experienced Khan’s diplomat – appeared on the stage and said: ” Oh Great Prince, among our co-travellers are people who know how to construct catapults which will throw such big stones that the station will not be able to withstand the siege and they will give up immediately when mangonels and trebuchets start to hit the town.” Khan begged them to construct these catapults as quickly as possible, although he had never heard of them before nor had he seen them. Then the three Polos started to work, ordered wood in big quantities, and sought out among the co-travellers there were a Nestorian Christian and a German who knew well how to build this efficient weapon. They built three catapults each of which could carry s stone of 150 kilos. The emperor insisted that they tried them in his presence, and when he saw the orbit of the stone he was delighted. Then he ordered the catapults to be brought to his camp in the vicinity of Sa-yan-fu. When the apparatuses were ready, one big stone was shot from each catapult to the town. They destroyed several buildings and caused panic among the population. The leaders of the besieged town began to consider what to do, but the opinion prevailed that it was some kind of magic and that they would all be killed if they continued to resist. They declared that they were ready to surrender under the same conditions as other towns and to become loyal citizens of the Great Khan. “So the men of the city surrendered, and were received on terms; and this all came about through the exertions of Messers Nicolo, Maffeo, and Marco; and it was no small matter. For this city and province is one of the best that the Great Khan possesses, and brings him in great revenues.”

But Marko Polo was not interested only in the battles. With his Mediterranean curiosity he admired even more the achievements of Chinese civilization, and he had unique opportunity to get acquainted with it at the peak of its glory. He was impressed especially by the “Heavenly city” of Kinsai, on the river of Yangtze, which he calls Coromoran. That city was saved from destruction by the Great Khan so that Marko experienced it in all its magnificence. The town extended in area more than a hundred kilometres and had 1,600,000 families, 12,000 stone bridges, which were so high that a big fleet could pass under them. There were twelve guilds, and each of them had 12,000 craftsmen’s buildings, in each of which 20 to 40 craftsmen worked. They also supplied other big Chinese towns with their products. The number of tradesmen and the town’s wealth is unknown. They lived in the greatest luxury and their wifes did no any physical work but enjoyed their luxurious robes and various entertainments. “These women are indeed very noble and angelic creatures!” There is a lake inside the town of almost fifty kilometres in area. Beautiful palaces are erected around it, as well as many churches. There are two islands in the middle of the lake, and a large building is built on each of them, equipped as the emperor’s palace. Any citizen can use it for a wedding or some other ceremony. Sometimes a hundred different feasts take place in these buildings. There are also luxurious apartments in them, where guests can sleep after the banquet. There are many pleasure boats for relaxation on the lake, on which the citizens of Kinsai embark after a work. When the Great Khan occupied that town he ordered a the guard of ten people to be on each bridge in case of trouble. Each watchman had a hollow instrument of wood and metal on which they struck every hour, day and night. Special precautions were taken in case of fire because there were many wooden houses in the town. The guards watched lest someone lighted a fire at an inappropriate time and without care. If this happened the offender was severely punished. There is a big tower in the middle of the town on which a wooden plaque hangs. When fire appears somewhere, the watchman strikes the plaque with the hammer so that the sound can be heard everywhere. All streets are paved by stone or brick. But the earth is left unpaved at the sides of the paving in order that the Khan’s horses may gallop. The main street is paved with two parallel ways of which each is ten paces wide. A space of fine pebble is left in the middle and under it arched conduits take water into the canals. Thus the road is always dry. The city of Kinsai has 3,000 baths to which water is brought from a source. There are hot baths which people can enjoy several times a month. “These are the most beautiful baths in the world; large enough for 100 persons to bathe in together. The ocean is only 40 kilometres from the town at a place called Gan-fu, where there is a town and an excellent harbour. Many merchant ships from India and other countries come there. And the great river Coromoran (Yangtze) flows from the city of Kinsai to that sea port, so that ships can sail to the city itself.” Marko was so impressed by the outside appearance of the town that he hardly noticed that Kinsai was one of the greatest centres of culture, education and art the world has ever known. There were more books in the libraries of Kinsai in Marko’s time than in the whole of the rest of Asia.

Million – Return to Europe – Travelling by Sea

Marko Polo spent seventeen years in the service of Kublai Khan. Those were the best years of his life, filled with exciting happenings, merchant business, diplomatic missions, love affairs. His father and his uncle also experienced the greatest honours and received prizes for their cleverness in trading and for their fidelity to the greatest ruler of the then world, the powerful Mongol political magician, Emperor Kublai Khan. But their lyfe-cycle and the adult years of Marko Polo had to end in their native soil of Europe and in their homeland Venice, the powerful trading republic to which they had come from the ancient region of Dalmatia and the small Mediterranean town of Korcula.

They communicate their decision to Kublai Khan with a heavy heart. The Khan at that time was laready seventy five years old. There was a great risk that the Great Khan would not release them from his service, because the Polos, and especially the young Marko, were dear to his heart. He had got used to them as extremely capable and not just ordinary persons coming from another civilization that, though it had not achieved the level of civilization of the greatest Asian country, China, from whom just the same he learned a lot. However, as always on their Odyssey through Asia, fortune smiled at them at the right moment. Bolgana, the first wife of the Persian khan Arghun wanted, before her death, a woman from her tribe in Mongolia to succeed her. Therefore, Arghun sent, in 1286, three messengers to Khanabalik asking the kindly Kublai Khan to choose a new wife for him among the beautiful Mongol girls. Kublai chose the princess Cocachin, a seventeen year old beauty. But the messengers, together with Cocachin, had to return to Khanabalik, because war broke out between the Mongol tribes en route. Marko Polo had then just returned from his successful mission in India. The Persian messengers suggested that he might help them to return to Persia by sea. Kublai Khan, although reluctantly, agreed to part company with his faithful dignitaries. He proclaimed the Polos his envoys to the Pope and the European kings and he gave them the small imperial plaque as a permit to secure them safe passage across his big empire. He ordered thirteen ships and enough food and equipment for two years of travel to be put at their disposal. Marko was amazed when he saw these big and powerful ships which were to carry them on their long journey. These were ships built with a double layer of planking, fastened with iron nails, and caulked with oakum. And since the Chinese had no pitch, the boats were coated on the bottom with a paste of quicklime and tung oil. There were sixty cabins in the interior of the boats, and the hold of the ship was divided by bulkheads into small, watertight compartments. In case whales rammed the vessel, the crew could confine the water to one compartment only, remove the cargo from it and repair the damage. This safety measure was not introduced into European vessels until the nineteenth century. As well as the big ships there sailed tug-boats with them in case of need. There were also, on each of the big boats, several smaller ones for fishing, anchoring and other work. The captain, with a crew of three hundred people, enjoyed really royal benefits and was regarded as a divinity.

So the convoy of the Polos, with the princess Cocachin, and with at least two thousand people, left the port of Zayton in spring 1292.

Polo interrupts his story at this point to disclose to us what he had heard about the mysterious island 1,500 miles away from the Asian continent. He calls it Chipangu (modern Japan) and speaks with admiration about its great richness. He mentions the imperial palace with the golden roof, and with floors and windows of golden plaques, and about the abundance of pink pearls which are put in the mouth of the dead before a funeral. Marko’s description of the richness of Japan excited the imagination of the European discoverers of the new world – among others of Christopher Columbus, and the cartographer Toscanelli, whose map was used by Columbus, and which put Japan seven thousand miles west of Portugal. At that time, the famous European discoverers did not have the slightest idea that Japan is double that distance away from Europe, and that, between it and Europe there is a whole continent, North America. The famous Kublai Khan heard also about the richness of Japan and sent there two armies of 150,000 Mongol and Korean soldiers combined. They managed to establish a bridgehead on the island of Kyushu, but the Japanese held them there. Then a storm smashed almost the whole of Kublai’s armada. From 4,000 ships only 200 of them managed to escape a terrible destiny. Marko Polo, as Kublai’s loyal diplomat explains this rare defeat of his master as due to a dispute between two generals (“barons”) who commanded the united forces of the Mongols and the Koreans. However, Kublai’s great strength lay in horses, not in boats. Marko speaks also about a curious event which happened to the Khan’s soldiers when they managed to disembark on Japanese soil and continued to make war there. When they attacked one of the towers of the defenders they killed all the warriors except eight of them whom they were unable to hurt. They had embedded under their skin gold and precious stones so that no steel could pierce them. European explorers in the nineteenth century confirmed these curious stories of Marko’s. That was usual way in which Japanese soldiers tried to be invulnerable.

For two months the Polo’s convoy was sailing from the port of Zayton to Indo-china (which Marko calls Champa). The king of Indo-china was paying annual tribute to the Great Khan of twenty elephants and much of the scented aloe wood.

Marko Polo and his escort were forced to stop in Sumatra for five months because of the southwest monsoons. As the natives were cannibals, Marko arranged a ditch filled with water round the camp on the coast and a strong guard. But, due to Marko’s diplomatic skill, these cannibals became very friendly and supplied our travellers with food. Then Marko saw, for the first time in his life, “nuts as big as human head” (coconuts), and the tree which gave flour for bread and cakes (sago). Marko says that fish in Sumatra is the best in the world. Marko’s escort drank palm wine after fish. They would put a cup under a cut in the palm tree and the vessel would be filled with white or red wine in a day and a half. Marko wrote that this wine is a cure for the sick spleen. When the cut branch does not give any more wine, the natives water the roots of the tree and wine starts to flow again very soon. The Malayans call this tree “gomuti” and they can also get sugar from it. Marko says that the liquid in the coconut “has a better taste than wine and than any drink that has ever existed”. Marko “saw” in Sumatra the mountain tribe whose members had tails like a dog.

Marko discovered divers searching for pearls in the shallow waters near Ceylon. As there were a lot of sharks in these waters, the tradesmen of the pearl shells would protect the divers by hiring a special caste of Brahmin sorcerers who would cast a spell on the sharks while the divers were picking up the shells. However, the sorcerers would remove their spell during the night lest rival divers should appear. It seems that the sorcerers did find some means of deterrence of sharks, as this practice was exercised for centuries.

Sailing towards the coasts of India, Marko Polo’s convoy reached the large nearby island of Ceylon. Marko sets here the story about the life of the Indian prince Sakyamuni, who became Buddha and founded the Buddhist religion. He was the son of the king of that big and rich island, who had an inclination towards the life of the saints from his early childhood. The king tried to persuade him to take over his throne. He built for him a big palace and ordered beautiful girls to entertain him with song, dance and other worldly pleasures. However, no girl managed to lure him into the world of pleasure, so that he remained alone, shut in the palace. His father did not allow any old or sick man to approach him, so that the young man was not aware about the inevitable end of every living being. But one day, the ill-fated prince rode to the nearby wood and saw a dead man on the road. When he asked what that thing which lay on the earth was, they told him it was a dead body. “Must all men die?” asked the prince with sorrow. He saw on the same road a toothless old man who could not walk. When he received, in this way, his first experience of the old age and death, the young prince returned to the palace and took a vow that he was going to look after That one who does not die and Who created him. Thus he reached the high mountains where he decided to live an ascetic life. If he were a Christian, Marko says, he would have become “the great saint of our Lord Jesus Christ” due to his good and pure life. When he untimely died, his body was brought in front of his father who loved him very much. The father ordered his servants to make a figure of gold and precious stones in his likeness and decreed that all had to worship it. The inhabitants of Ceylon proclaimed him the greatest of all their gods and they idolised him. Marko adds that the young prince died four times and each time he was reborn as another animal: ox, horse etc. But he was reborn as a god only after he had died eighty four times. Thus the Europeans learned from Marko’ story about the noble founder of the Buddhist religion. Although a member of another Church, Marko speaks with sympathy about the young Buddha. He confirms this affection for him by emphasizing that the Great Khan sent for Buddha’s relics from his tomb on the top of the mountain.

Marko shows similar benevolence towards the Indian Brahmins and yogis. He says that the Brahmins are the most honest tradesmen in the world, that they never lie and that they help foreigners to sell their goods without profit to themselves. They hate all killing and even the killing of animals. They believe very much in various signs and omens, as shades, and especially the movements of the tarantula spider. He says that yogis believe that all things have souls, and that they do not wish to kill either worm or lice. They do not use plates but they eat from dry leaves and they drink only water. They never mix with women. They sleep naked in nature without any covering and they reach a very old age.

However, Marko liked more the luxurious royal courts than the shacks of the poor. He was especially impressed by the Indian king from the Coromandel coast. The king did not wear any clothes because of the warm climate and he was always adorned with precious decorations; among other things, with a medalion of diamonds, a necklace of 104 pearls and rubies, gold bracelets on hands and legs and with rings on the fingers of both hands and legs. Five hundred women, together with many noblemen, accompanied the king wherever he went. When he died and was cremated, his subjects were throwing themselves in the fire in order to follow him. Marko mentions also the custom of suttee when wives throw themselves on the funeral pyre after their husband.

Marko’s frequent observation of the ritual of fire, as the way to achieve the divine life in heaven, speaks also about his restless, fiery temperament which incited him always to thirst after new knowledge and new adventures of both spirit and body.

Although Marko introduced India to Europe, with his accurate observations of the customs and the way of life of Indian inhabitants two centuries before Vasco de Gama – who was later celebrated as the discoverer of that “unknown” subcontinent – he could not ignore the fantastic legends extant before the time of his travels. One such story is about “the island of women” which was visited by men from their own island only in spring time. Another fable is that about the “roc” bird from Madagascar, which was so strong that it could carry three elephants. Even this fantastic story might prove to be true as was the case with other descriptions Marko’s. This bird is mentioned in the “Arabian Nights” from the seventh century in the story about the sailor Sinbad.

Finally, after more than two years of toilsome but exciting travelling across the south seas, the convoy arrived in Persia. Marko does not mention at all Scylla and Charybdis through which his expedition passed, all possible storms and distresses, the attacks of various native tribes and diseases, unbearable heat, rotten food and water. He summarizes all this in one single sentence when he says that from six hundred travellers, not counting the crew, only eighteen survived the journey.

After arrving at their destination, the court of the Persian shah Arghun, the Polos learned that he had died, but his son Ghazan resolved the awkward situation and decided to marry the princess Cocachin, who had been intended for his father. The Polos rested in Persia for eight months from their tiresome travelling and there they received the news that their friend and protector, the Great Khan, had died. The man they must thank, to a great extent, for their riches and their rich life filled with exciting events. The princess Cocachin was cried while she was bidding farewell to Marko Polo, and our convoy converted itself into a caravan. The Polos arrived over land to Trebizond on the Black Sea, where they were happy to meet the familiar faces of Venetian and Korculan tradesmen. But they experienced their first setback in that first port in touch with the Christian world. Thieves stole from them a big quantity of golden coins.

From Trebizond, via Constantinople and the Aegean Sea, they finally entered their Adriatic Sea and, by that well-known trade route passed by Marko’s native Korcula. That was in 1295, exactly 701 years ago.